The Future of the Insurgencies of Afghanistan

2018 saw much continuity in the state of the insurgencies of Afghanistan, with the Taliban and Islamic State — Khorasan Province (IS-KP) being the most prevalent threats.

Other groups such as the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Lashkar-e Islam (LeI) have also remained ever present in the Afghan security situation in the border regions. Signs of continuity include the Taliban’s control over rural areas across the country and their ability to move with relative freedom in their controlled/influenced territory. Despite frequent ANSF operations supported by US and NATO airpower, little change has been observed regarding actual Taliban territorial control at a broader level. The Islamic state also continues to hold on to a small but important area of territory in East Afghanistan, with much of their activity being centred around Nangarhar Province and suicide attacks in Kabul and Jalalabad.

Change has come in a variety of forms, with perhaps the most substantial being President Trump’s decision made at the end of the year to withdraw approximately 7,000 US personnel from Afghanistan out of the 14,000 currently stationed there. As well as this seemingly abrupt change (which many analysts expected) there have been some changes to Afghanistan’s security landscape at a provincial level as well. For example, IS-KP was forcibly removed from their small enclave in Jowzjan Province’s Darzab and Qush Tepa districts during a swift Taliban offensive which saw ANSF personnel in the region largely side-lined. The dramatic reduction of the IS-KP presence in the north of the country has the potential to shift regional priorities of Afghanistan’s neighbours, who have long been wary of an Islamic State presence so close to their own borders.

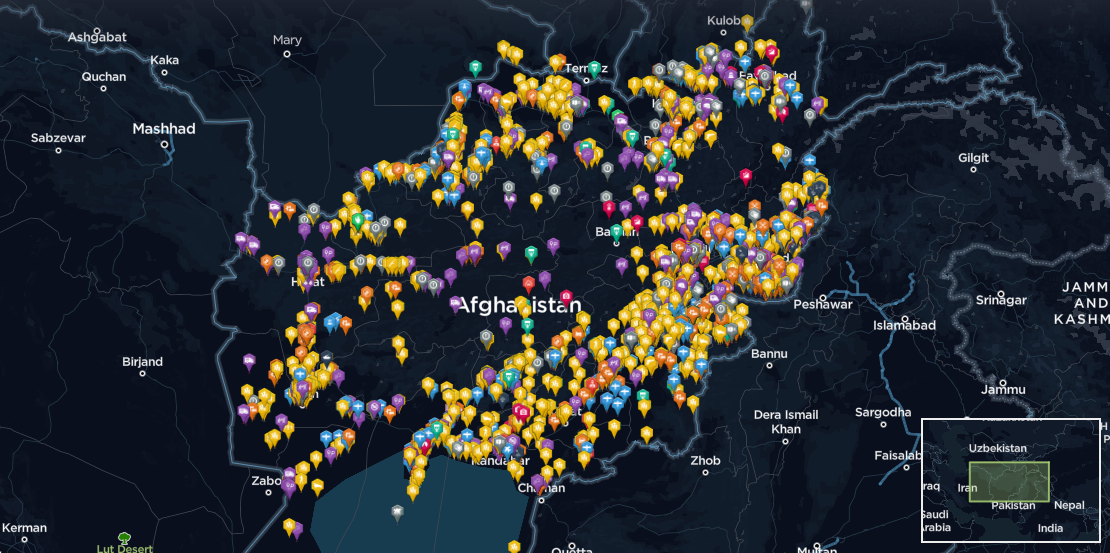

Looking forwards, evidence as to what can be expected in 2019 can be found from looking at patterns observed throughout the course of 2018 using Intelligence Fusion’s incident map. The map shows a vast collection of incidents reported throughout the period ranging from local level crime and protests to major complex attacks in Kabul.

Figure 1: Incidents in Afghanistan recorded throughout 2018.

Areas which see high levels of fighting generally are where both security forces and the Taliban have significant personnel and influence in the area, rather than where one side dominates. The relative lack of incidents in Taliban controlled areas can suggest that the ANSF is mostly on the defensive, and incursions into Taliban controlled territory are less common (albeit still frequent) than Taliban attacks on ANSF positions. The following section will provide further analysis of some of the most significant areas of the country in order to try and shed light on what can be expected from the Taliban in the upcoming year.

Future of the Taliban Insurgency

Throughout 2018, the Taliban kept pressure on the ANSF in every province of the country. At one end of the spectrum, Ghazni Province, Faryab, Nangarhar and Zabul have all reported high volumes of incidents, mostly skirmishes and airstrikes carried out in support of ANSF ground personnel. At the other end, Bamiyan Province, which the Taliban claim to have control of just 5% of[1], has reported very few incidents and generally remains calm. An exception to this was calm was an ambush of an ANSF convoy in the Ghandak district in October. Other provinces such as Balkh have followed a different pattern to ones such as Ghazni (where fighting occurs in almost every district.) In Balkh, a high volume of combat related incidents were reported throughout the year, but the incidents are mostly restricted to the Chaharbulak, Chimtal and Dowlatabad districts. The observation here is that whilst the Taliban control is dominant across much of Afghanistan, the Afghan Government does still have the ability to maintain a level of security in localised areas such as the districts of Balkh not mentioned above and Bamiyan using political figures who are closely ingrained into the local society.

Taliban strategy at a district level has always been heavily influenced by local concerns and as a result, the group has traditionally been sound at ingraining themselves into local populations. This social integration is much the case in the rural Pashtun regions of the country that are more inclined to provide passive support to the group. The Taliban have been able to do this using a series of means, but perhaps the most influential have been assets such as the Taliban court system which provides swift justice to those who live in Taliban areas.

The functioning Taliban courts have acted as an extension of the Taliban shadow government, which has aimed to build a functioning state system, familiar with local sensitivities, where the Afghan Government and their foreign supporters have failed. This tactic has served to drive a wedge between the government and the people they govern, creating an environment in which the Taliban can thrive and continue to reinforce their tactical victories with their interpretation of sound governance. With the success of this strategy in mind, it can be assumed that the Taliban shadow government system will continue (and consequently, airstrikes will continue to target commanders involved in the shadow government.)

A major Taliban offensive which began in Oruzgan provides a high-profile example of the Taliban attempting to isolate the government from the population, one area at a time[2]. The fighting started late in October, and specific details were slow to emerge from the isolated area. Regardless, many observers instantly noticed the fact that the Taliban attackers who were drawn from mostly Pashtun areas were opposed by Hazara militias. The seemingly binary ethnic composition of the opposing sides led many to view the fighting through the lense of ethnically charged fighting, which has been prolific throughout the history of Afghanistan. In reality the situation was somewhat different but highlights a similarly concerning conclusion that will have an impact on the government’s legitimacy in the future, that the government struggled to protect a pro-government area from the Taliban.

The inhabitants of the Kondolan area of the Khas Oruzgan district, where the offensive started, were largely pro-government and had kept their independence from Taliban control until the fighting began. The area boasted a higher level of self-rule than many areas, and as a result ANSF presence in the area was relatively minimal. The opposition to the Taliban was led by a Hazara militia commander named Shujai, whose history of crime and corruption made him an infamous figure in the area. The fighting continued, and what started as a small skirmish quickly escalated into a large scale offensive in which the Taliban pushed deeper into Hazara/pro-government areas and into neighbouring Ghazni Province. Heavy fighting took place in the Jaghori and Malestan district, where ANSF reinforcements had been sent. However, reports quickly emerged of high casualties among the popular Afghan commando forces, suggesting that Afghan Ministry of Defence press releases were offering a warped vision of what was actually taking place.

Figure 2: Hoqtul and Anguri villages of Jaghori (Ghazni) where much of the fighting took place. Security forces in the area feared that if the villages fell the to the Taliban, the route would be clear to the Jaghori district centre.

The pace of fighting slowed towards the end of November, and security forces claimed to have repelled the Taliban attack and forced their fighters to retreat. This was not quite the situation on the ground, as fighting was reported after the ANSF’s declaration that the Taliban had been pushed back. The whole episode exposed the ANSF’s inability to protect areas that are self-declared pro-government areas. The sheer amount of time it took for ANSF personnel to be deployed to the area in significant numbers allowed the Taliban to push far into pro-government territory before coming across organised operations. This is not to say that the Afghan Government is universally unable to support pro-government areas, as the ANSF’s capacity changes significantly depending on the area in question. Nevertheless, pro-government areas are likely to have observed the fighting with concern, and questioned the ANSF’s ability to provide military support capable of protecting them.

The Taliban have pursued a strategy of applying pressure to security forces across the country on a daily basis through frequent attacks on checkpoints and convoy. Generally the attacks have been low level attacks, with small isolated checkpoints falling to the Taliban, however reports of major ANSF positions falling are common. Going forwards, there are a number of areas that appear to be under particular threat from Taliban militants, including provincial capitals and a host of district centres which are thinly held by security forces.

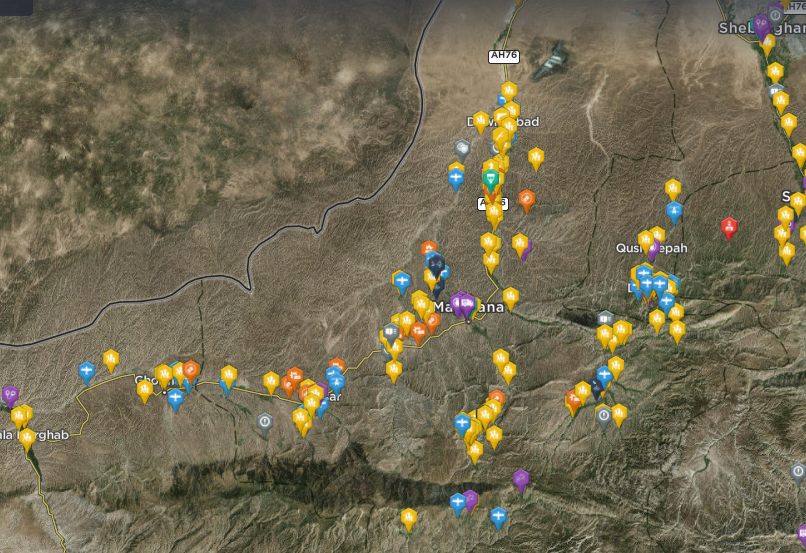

Maymana, the provincial capital of Faryab Province has been under sustained pressure from the Taliban throughout 2018 and provides an example of an urban centre under pressure. The surrounding districts are highly volatile, with the Pashtun Kot and Ghormach districts believed to be controlled by the Taliban (according to data provided by Long War Journal.[3]) The above image shows the spread of significant incidents in the Maymana are in 2018, with many smaller attacks likely to have occurred without any form of documentation. The Ghormach and Qeysar districts to the west of Maymana both host a large number of violent incidents, including the major Taliban attack on the ANSF ‘Chinese Camp’ in April 2018. To the north of Mayaman, in the Dowlatabad and Koh-e-Sayyad districts, the heavy fighting is consistently reported along the main road leading to the north of the Province and towards the border with Turkmenistan. To the south, the Taliban have a large influence in the restive Sar-e-Hauz district, and in December released images claiming to show their fighters at the Sar-e-Hauz Dam. The level of Taliban influence in the surrounding rural areas means that an attack on Mayaman similar to those seen in Ghazni and Farah would leave the ANSF hard pressed to reinforce their personnel in the city.

Figure 3: Maymana and the surrounding area.

Implications of the partial US withdrawal from Afghanistan

President Trump’s decision to withdraw approximately 7,000 troops from Afghanistan was not a surprise for many, although the abruptness seemed to have caught all observers off guard. The decision will see the US force in the country halved, although exactly what forces are to be withdrawn is not currently clear (nor is the timeframe of their withdrawal.) The impact of the withdrawal is hard to gauge, and without confirmation of exactly what assets are being withdrawn most guesses will be merely speculation. However it is worth noting that US personnel are involved in very few of the skirmishes reported across rural Afghanistan meaning the impact could be less than anticipated. Instead, US and NATO involvement is largely restricted to training and special forces operations.

In the wake of the US withdrawal, there will be approximately 8,000 NATO personnel, whose future remains unclear in the wake of the decision, although a similar drawdown is plausible. The withdrawal leaves the Afghan National Security Forces more isolated than ever at a time when the Taliban are husbanding their strength and showing they have a significant military capacity. The ANSF consists of approximately 315,000 personnel but is generally believed to be taking unsustainable casualties during the daily skirmishing across the country. Without the additional US personnel it is doubtful there will be significant changes on the ground, but if the withdrawal involves a reduction of US air assets it can be assumed that the Taliban’s capacity will increase significantly. Without the constant possibility of US/NATO airstrikes, Taliban militants will be offered more ease of movement and will also find their semi-conventional attacks on urban centres are less likely to be interdicted.

Lastly, the Taliban have recently engaged in peace talks involving the US, Pakistan and a host of other countries in the UAE. The results of the talks have not been immediately clear but it is worth noting that throughout December, when the talks were taking place, the intensity of fighting did not change. Furthermore, the Taliban continue to stick to their insistence that they will not negotiate with the Afghan Government, who they accuse of being a puppet of the USA. Instead, the Taliban will only communicate directly with US officials. It is doubtful that Trump’s decision to withdraw US personnel was the result of the peace talks, nevertheless the decision will have a substantial impact. The Taliban demand that US forces be removed from the country, and Trump’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan (albeit partially) suggests that no matter what, US personnel will withdraw. The Taliban therefore, are faced with the familiar position in which they can ‘wait out the storm’ under the knowledge that domestic pressure is forcing the USA’s decision making process.

Taliban Use of Social Media to Support Operations on the Ground

With the US and NATO’s involvement spanning nearly two decades, methods of fighting have been forced to evolve. An example of this is the Taliban’s use of social media, which is carried out to support and legitimise their activity in the ground. The Taliban run a number of social media accounts in various languages and are particularly active on Twitter. The social media accounts act as official spokespeople for the group, and spread high volumes of images, videos and posts claiming to show attacks, civilian casualties after airstrikes as well as Taliban militants occupying abandoned ANSF bases. On Twitter, the Taliban support the accounts of their spokespeople with a series of other accounts (which do not openly claim to be pro-Taliban) in order to flood ‘hash tags’ with pro-Taliban rhetoric.

The Taliban’s manipulation of social media may to some seem as a trivial issue in a military situation, however, as an insurgency the spreading of Taliban rhetoric to a broad audience is hugely important. By using social media in multiple languages, the Taliban have been able to spread their version of events on the ground which are generally under reported in international media. The result being that incidents such as an ANA helicopter crashing due to a malfunction may be interpreted as a helicopter being shot down due to a fast, effective and focused social media disinformation campaign. The Taliban tend to be able to disseminate their own version of events far quicker than the Afghan Government or Resolute Support, meaning that by the time anti-Taliban narratives are released, it is often too late to make an impact.

Resolute Support and the Afghan Government have gone some way to try and counter the Taliban narrative which is dispersed across social media, however their response has been slow and relatively cumbersome. The immediate result has been a rise in situations seemingly unique to the modern era in which accounts affiliated with Resolute Support/US military have faced off in a comments section of a social media post with accounts affiliated to the Taliban. Whilst such exchanges may seem almost laughable, they do still represent an important aspect of an ongoing attempt to ‘win hearts and minds’ in an insurgency-context, in which the way a party is perceived is vital and represents a ‘centre of gravity’ which must be addressed.

Islamic State’s Presence in Afghanistan

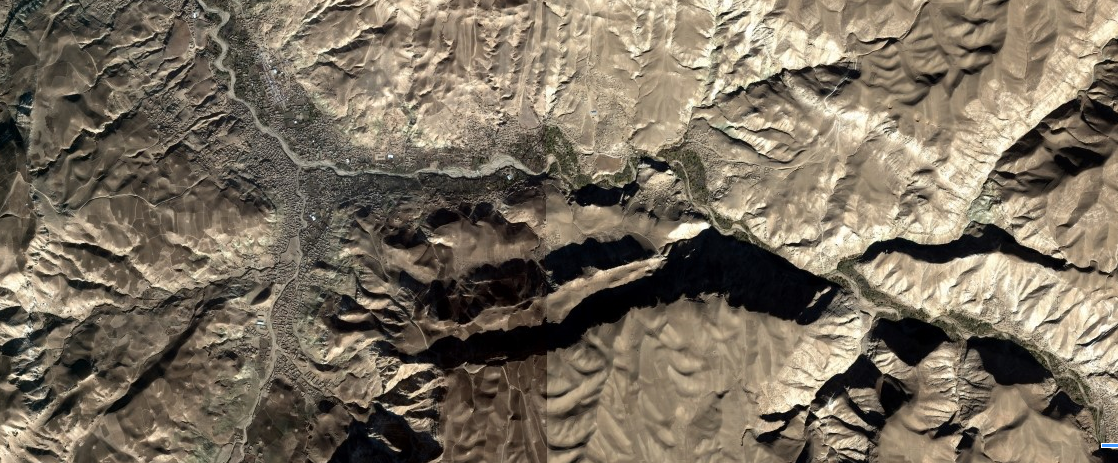

The fall of Islamic State’s stronghold in the Darzab and Qush Tepa districts came shortly of the death of Qari Hekmat, the charismatic commander of the group who forged IS-KP’s enclave in the north of the country. Hekmat was killed by a US drone strike in 2018, but it was the Taliban attack which followed shortly after Hekmat’s death which crushed the IS-KP presence. The attack itself involved Taliban militants gathered from across Afghanistan, with some sources claiming that militants were drawn from as far away as Helmand. The offensive ended with the remaining IS militants in the area handing themselves over to security forces, who evacuated the prisoners out of the province as media coverage gradually lost interest.

Figure 4: Satellite image of the Darzab district, Jowzjan, where IS-KP made a last stand. (Source: Bing Maps)

IS-KP’s northern enclave and its eventual destruction led to a change in the regional politics of Afghanistan’s Central Asian neighbours. Central Asian states and Russia have been cautious of the presence of the Islamic State so close to their border, despite many analysts doubting whether the northern enclave’s commanders had any broader regional goals such as carrying out attacks in Central Asia. In fact, it was never confirmed as to whether Qari Hekmat swore allegiance to al-Baghdadi. Regardless, the Central Asian states did have some cause for concern, as many of the fighters operating in Northern Afghanistan are from ethnicities present in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Russia routinely pointed towards presence of Islamic State in Afghanistan (particularly in the North) as a justification for Russian involvement in the country. With the IS-KP northern enclave being removed, concerns regarding the threat of IS among Central Asian capitals may have been subdued somewhat, whether or not his will impact Russian rhetoric regarding their involvement is unclear.

In the east of Afghanistan, IS-KP continues to have a significant presence, centred mostly in the Achin and Deh Bela districts of Nangarhar and parts of Kunar Province. Clashes between the Taliban and IS are common (although often go unreported) with other groups such as Lashkar-e Islam also being involved in areas rich in Taliban and IS-KP activity. The US air force has also carried out a campaign of frequent airstrikes targeting IS commanders and gatherings in remote areas. The strikes have not yet contributed to a significant reduction in IS-KP territorial control but have served to limit the capacity of the group to an extent by interdicting their movement and reducing their battlefield capacity to a limited extent.

IS-KP’s strength does not necessarily come in the form of territorial control, instead the group’s lethality is based in their ability — and willingness — to use force in built up civilian areas such as Jalalabad and Kabul. Both the Taliban and IS-KP carry out frequent attacks in both cities but IS-KP attacks can generally be characterised by their lethality and high numbers of civilian casualties. IS-KP is also believed to have built up a network of cells in Kabul, recruiting from the city’s population, including young educated recruits attracted to IS-KP’s cause.

Conclusion

Throughout 2018, skirmishes, IED attacks and airstrikes were reported on a daily basis, with rural Afghanistan acting as a host to many of them. Provincial capitals such as Maymana, Ghazni, Farah and Kunduz still remain in government control, but the firmness of the government’s grip was placed under the spotlight during high profile, large scale attacks by the Taliban throughout the year. Major cities such as Kabul and Jalalabad, whilst controlled by the government, play host to substantial numbers of suicide attacks, IED related incidents and targeted killings, highlighted the nature of the tenuous security situation.

Despite the overwhelmingly negative security situation in Afghanistan, there have been some signs of progress, albeit limited. The well-publicised Eid ceasefire for example, whilst short lived did act as a vital first step in bringing the Taliban and other parties together for meaningful peace talks. Ongoing peace talks between the Taliban and other parties towards the end of 2018 have also been largely ineffective at a broader level (exact details of what was discussed are not clear at the time of writing) but represent a small step towards compromise. To summarise, it is likely that 2019 in Afghanistan will be highly similar to 2018, in that the Taliban will continue to stage attacks against security forces across Afghanistan, IS-KP will likely continue to pose a significant threat and NATO forces currently engaged in Afghanistan will continue to search for an escape option whilst saving face.

[1] http://alemarah-english.com/?p=39651

[2] https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/taleban-attacks-on-khas-uruzgan-jaghori-and-malestan-i-a-new-and-violent-push-into-hazara-areas/

[3] https://www.longwarjournal.org/mapping-taliban-control-in-afghanistan