Could what happened in the Middle East predict Islamic State’s takeover in Africa?

Comparing the success of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria with its growing threat in Africa

Report by Viraj Pattni and Max Taylor

While Islamic State’s presence in its former stronghold of Iraq and Syria has waned since the loss of its final territory over two years ago, the group – and its ideal of a global caliphate – remains very much active, and increasingly focused on the African continent. Indeed, while the capabilities of the group have diminished in the Middle East, its activities and territories in Africa have grown, with many reports now predicting that the continent will become the group’s new ‘centre of gravity’. The speed with which Islamic State was able to seize territory and found its caliphate in Iraq and Syria stunned many observers, and with the group now spreading across Africa, it is worth noting the tactics used by the group to set up and sustain its original stronghold in the Middle East, and the factors that allowed it to flourish, and comparing it to those in its various ‘provinces’ in Africa. What allowed ISIS’s initial rapid growth in the Middle East? How do the various groups across Africa operate? And just how likely are we to see an Iraq and Syria-style Islamic State takeover, and self-sustaining caliphate, take place in Africa? Our Senior Regional Analyst for the Middle East and Asia, and our Senior Regional Analyst for Africa take a look at the different activities seen by ISIS and its affiliates.

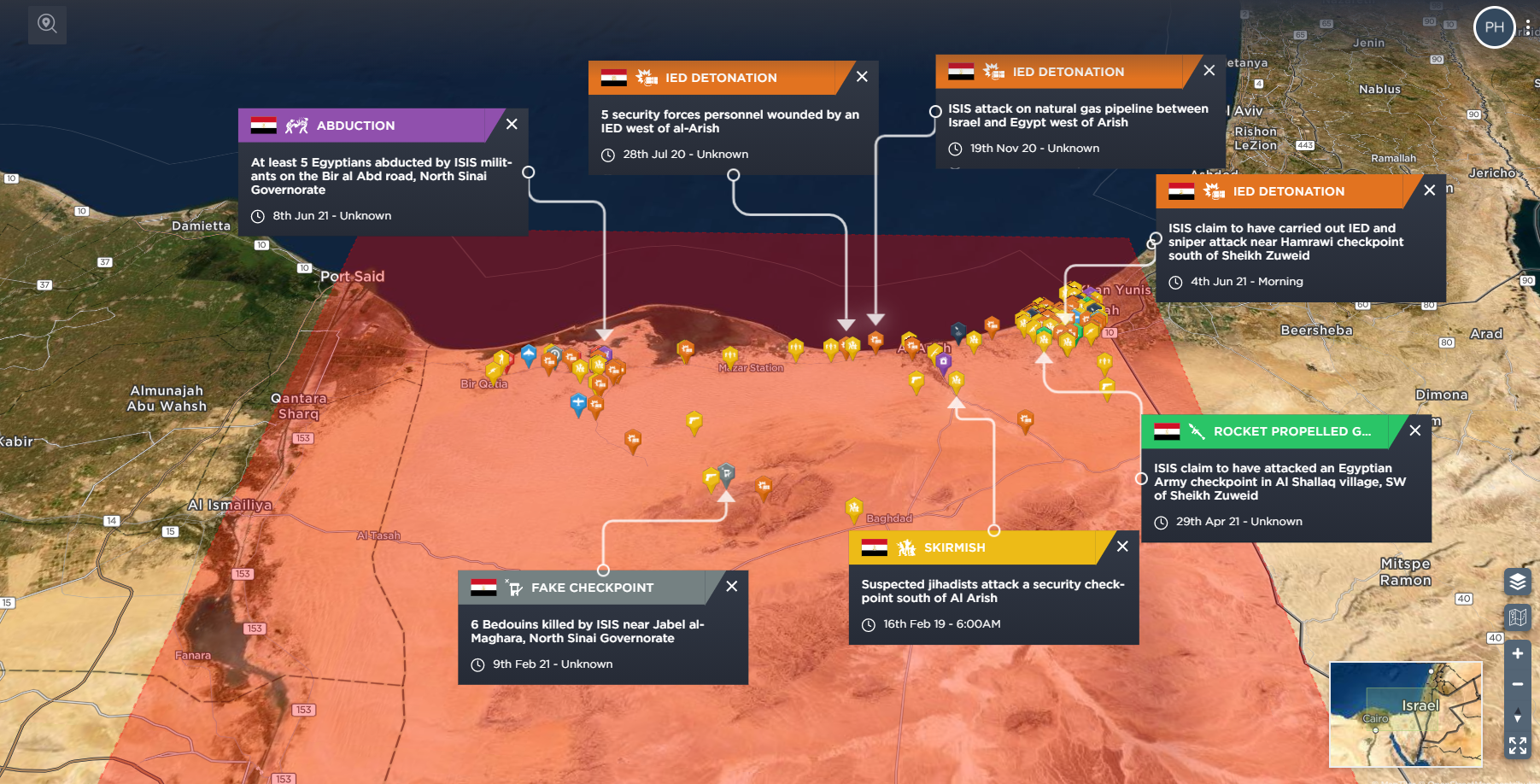

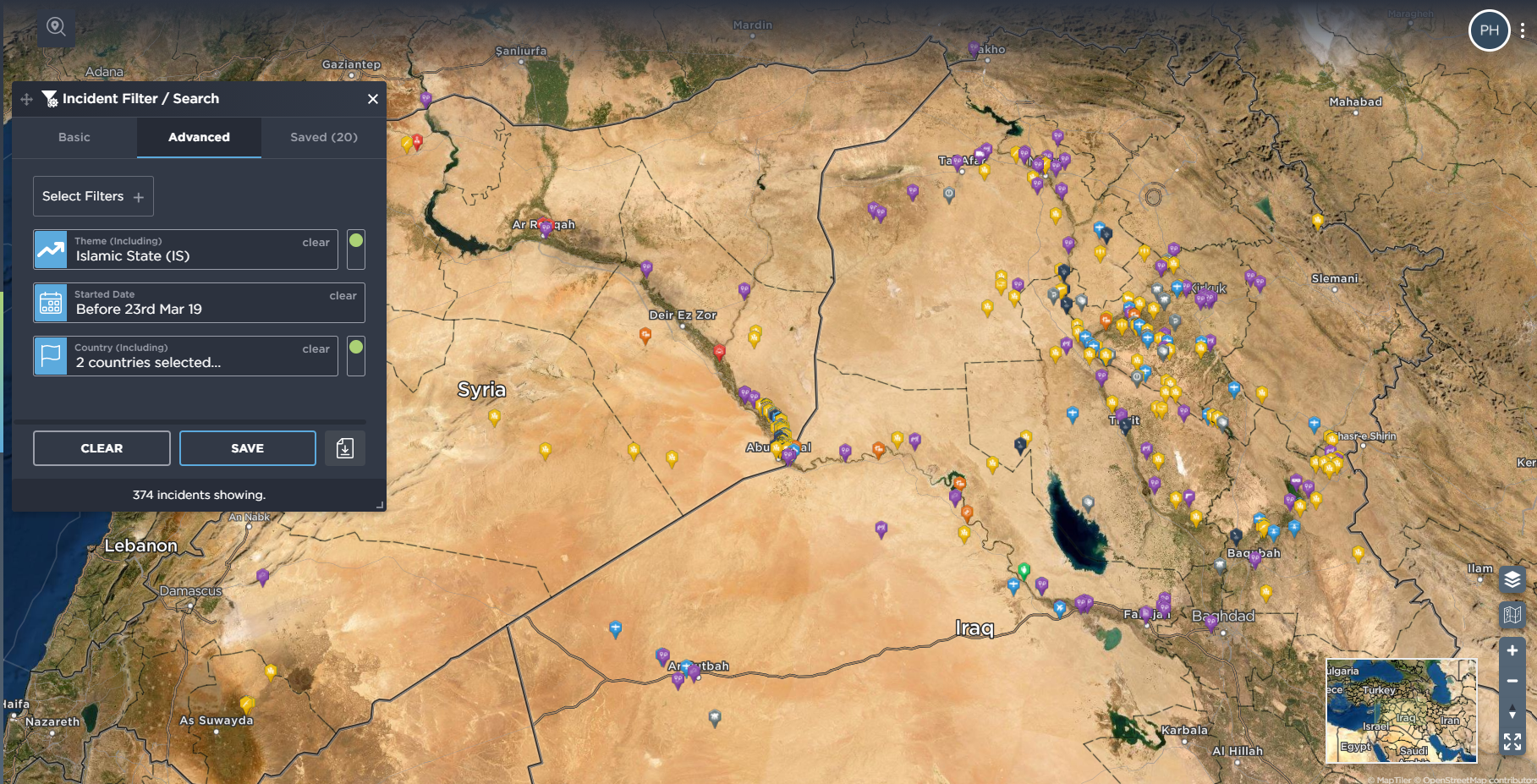

Snapshot of incidents involving ISIS in Iraq and Syria from 2015 until the loss of their final territory in March 2019 [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

ISIS success in Iraq and Syria

ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) and its rapid growth in the Middle East region can be explained as the result of a broad variety of factors combining to create an environment in which extremism flourished. These factors, such as poor social conditions, poor governance and sectarian tensions were then provided with catalytic events such as the Syrian Civil War and the US-led intervention in Iraq. Over time, these events and conditions worsened the region’s security situation, permitting the rise of armed groups and sectarian inter-communal fighting. Within this context, ISIS was able to manipulate the security vacuum in both Iraq and Syria, seizing territory, attracting new recruits and developing its own caliphate in the process.

As fighting progressed, ISIS found that it was able to tap into a feeling of resentment and disenfranchisement among certain groups to recruit fighters and conquer territory with relative ease. At their peak, ISIS controlled major population centres such as the Syrian city of Raqqa as well as the Iraqi city of Mosul, showing the group had made the step from insurgency to near-conventional tactics. Security forces in Iraq and Syria in many cases collapsed in the face of ISIS attacks, often characterised by high-speed assaults on isolated positions followed by acts of extreme violence against captured soldiers or civilians. Local security forces suffered from years of neglect and corruption, and despite equipment and training provided by foreign forces, were often left poorly equipped and led in vital moments. As ISIS continued to seize more territory, the group also took control of a number of oil production facilities, particularly in Syria’s Deir Ezzor Province on the border with Iraq.

After the capture of oil production facilities, ISIS was able to maintain high levels of production (estimated at 70,000 barrels per day at their peak) in order to generate revenue. The oil produced in ISIS territory was then sold to a number of buyers in neighbouring countries via local traffickers. Oil produced in ISIS-controlled territory is reported to have been sold (via intermediaries) in countries such as Jordan, Iraq, Turkey and even to the Syrian Government itself.

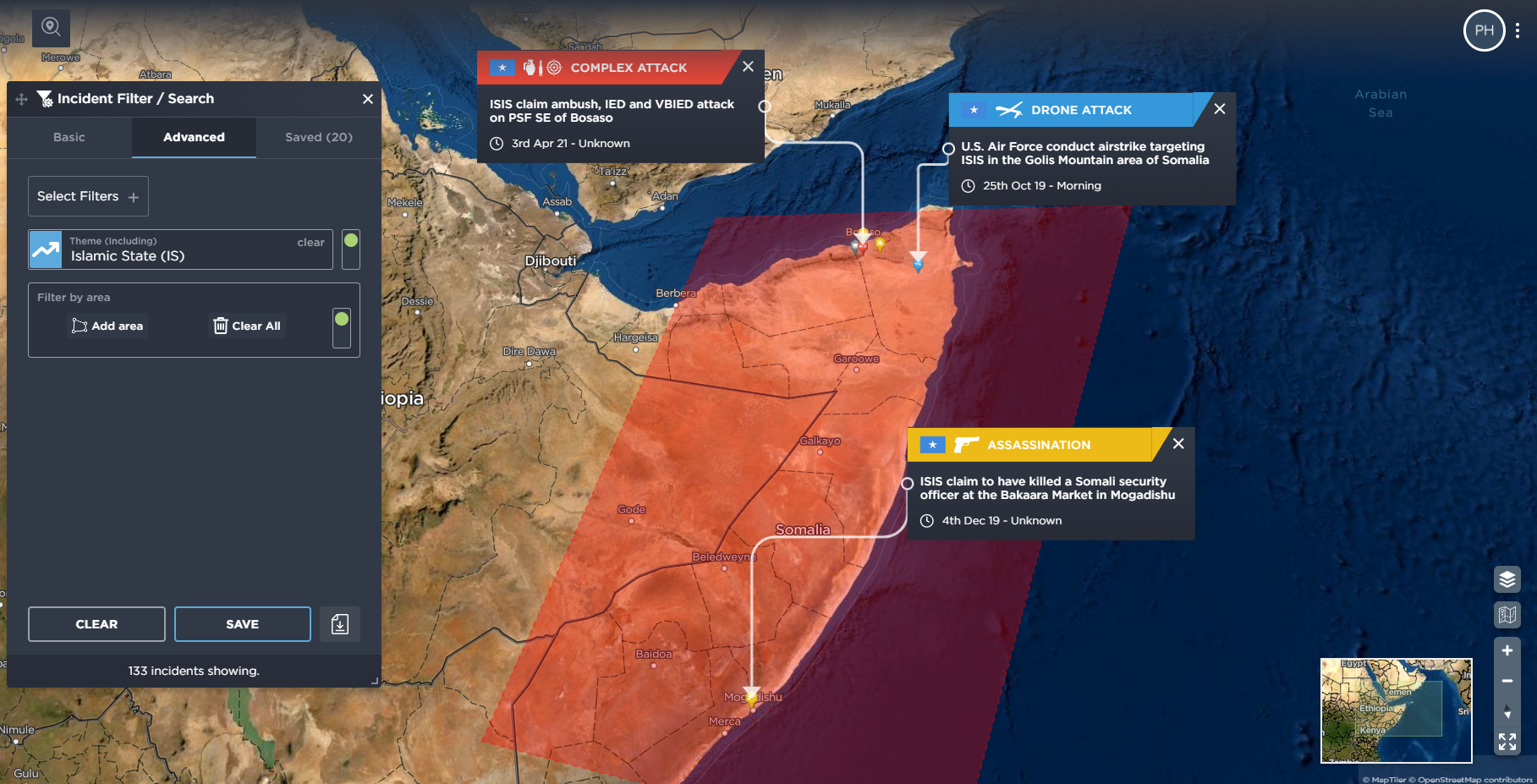

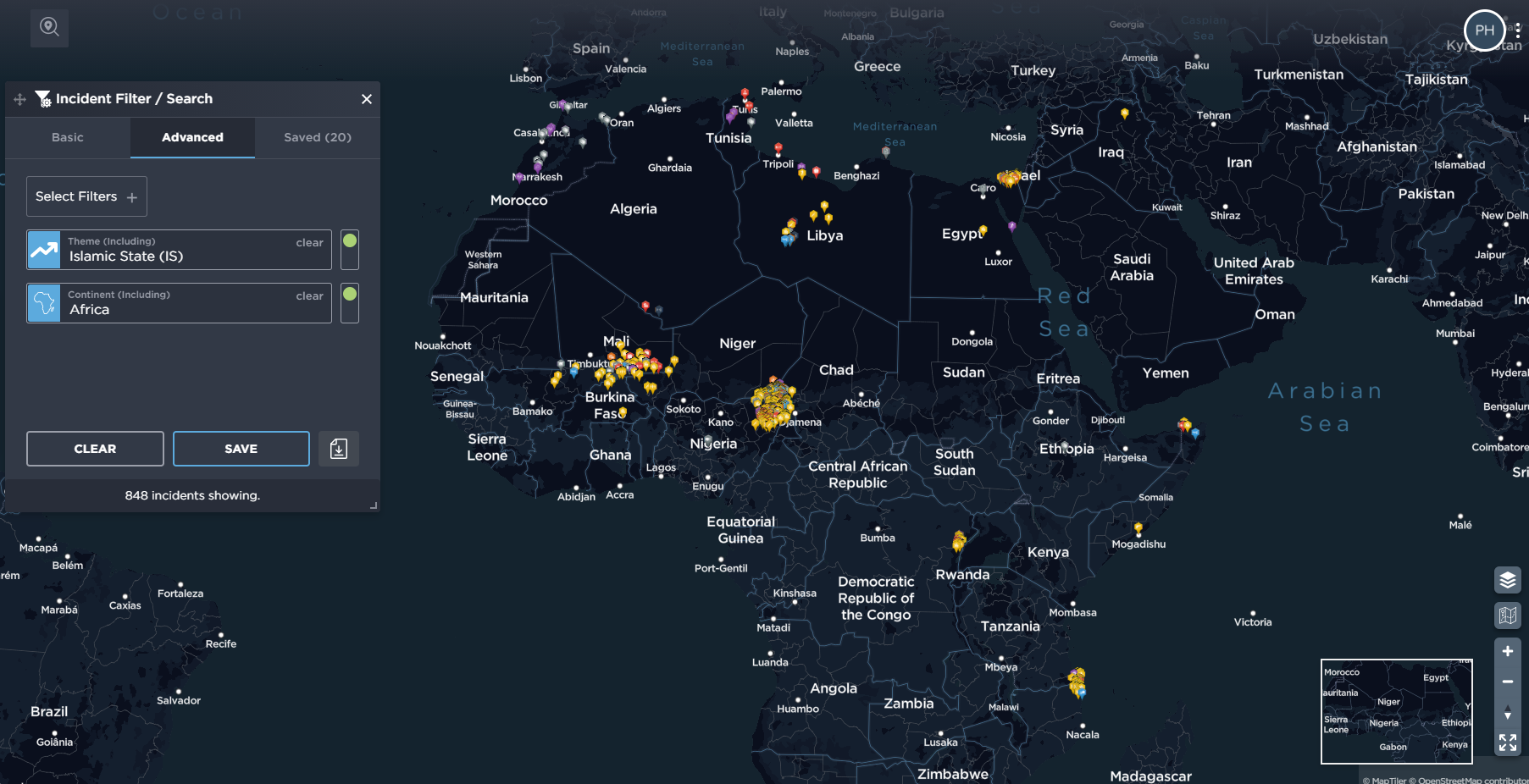

Islamic State activity in Africa [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

ISIS in Africa

When ISIS was at the height of its power in Iraq and Syria, between 2014 and 2016, it forged links with more than 40 organisations in dozens of countries and established formal links with groups in eight countries. Presently, there are eight provinces, or ‘wilayahs’, that are active in Africa: ISIS Sinai, ISIS Algeria, Islamic State in Fezzan, Barqah, Tarabulus (all of which are in Libya), ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province) which includes ISGS (Islamic State Greater Sahara), ISS (Islamic State Somalia) and, most recently, ISCAP (Islamic State Central Africa Province). Attacks have also been claimed in Tunisia although the group has not carried out a successful attack in Morocco, where ISIS cells have been dismantled. ISIS has referred to its wilayahs as ‘semi-independent’, but questions have been raised as to the depth of the link between ISIS central command and wilayahs in Africa and if, or to what extent, ISIS are directing operations in Africa. Rather than being exported into Africa, ISIS have coopted local jihadist groups that have pledged allegiance to ISIS. The objectives of these local jihadist groups may differ from ISIS as many have existed long before they pledged allegiance.

The early success of ISIS in Libya meant that the country was once seen as a potential hub for the group [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

ISIS Libya

ISIS demonstrated its ability to hold and govern territory outside of Syria and Iraq when they took control of the Libyan coastal cities of Derna and Sirte in 2015. As seen in Syria and Iraq, ISIS were able to exploit a power vacuum within the country to establish themselves, and by taking control of Sirte, a major city located near Libya’s oil crescent region, with around 3,000 fighters based in the city at one point, we can see why Libya was once thought of as a potential hub for the group. ISIS also exploited the division between Libyans, recruiting disillusioned pro-Gaddafi supporters and those who held radical Islamist views. A large influx of foreign fighters strengthened the ranks and capabilities of ISIS, with the largest contingent of foreign fighters arriving from Tunisia, a country affected by political dysfunction and a dwindling economy. ISIS’s experience in Libya thus far serves as an illustration of how the group can exploit instability in North Africa and the wider region.

ISIS, however, failed to capitalize, and Libyan forces, supported aerially by the U.S., displaced the group from Derna and Sirte, and the group’s activities in Libya have reduced since they lost control of the aforementioned cities in 2016. Further airstrikes followed in southern Libya, destroying ISIS camps, further restricting the group’s presence in Libya and forcing it to shift to asymmetric tactics. The group continues to claim attacks in Libya and have demonstrated they retain the capability to carry out complex and sophisticated attacks in the present day. Continued political instability and the threat of renewed fighting between rival armed groups could see the resurgence of ISIS activity and with the group active in southern Libya, including in and around the Harouge mountains in recent years, attacks on security installations located near towns or near oil fields is probable.

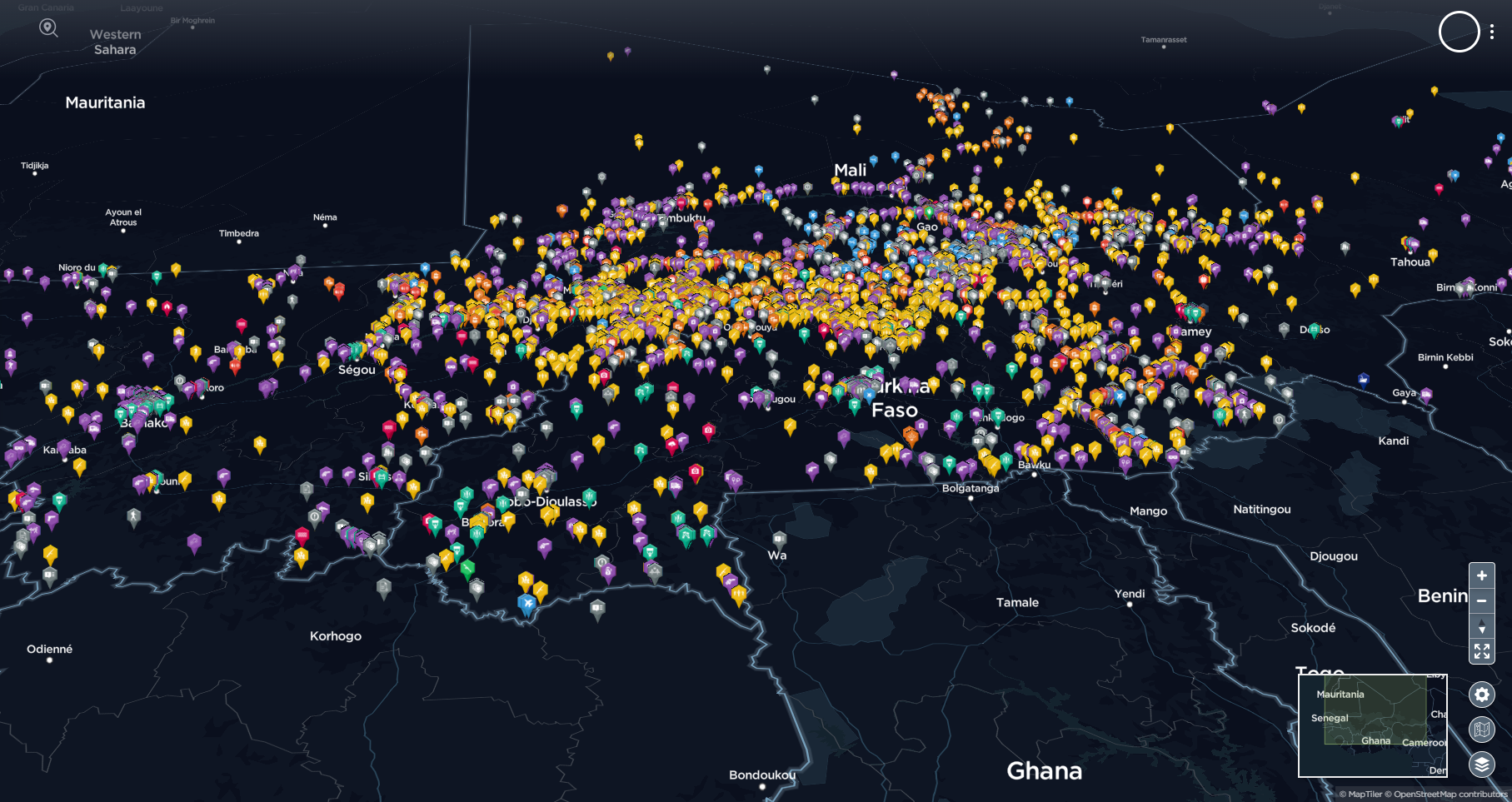

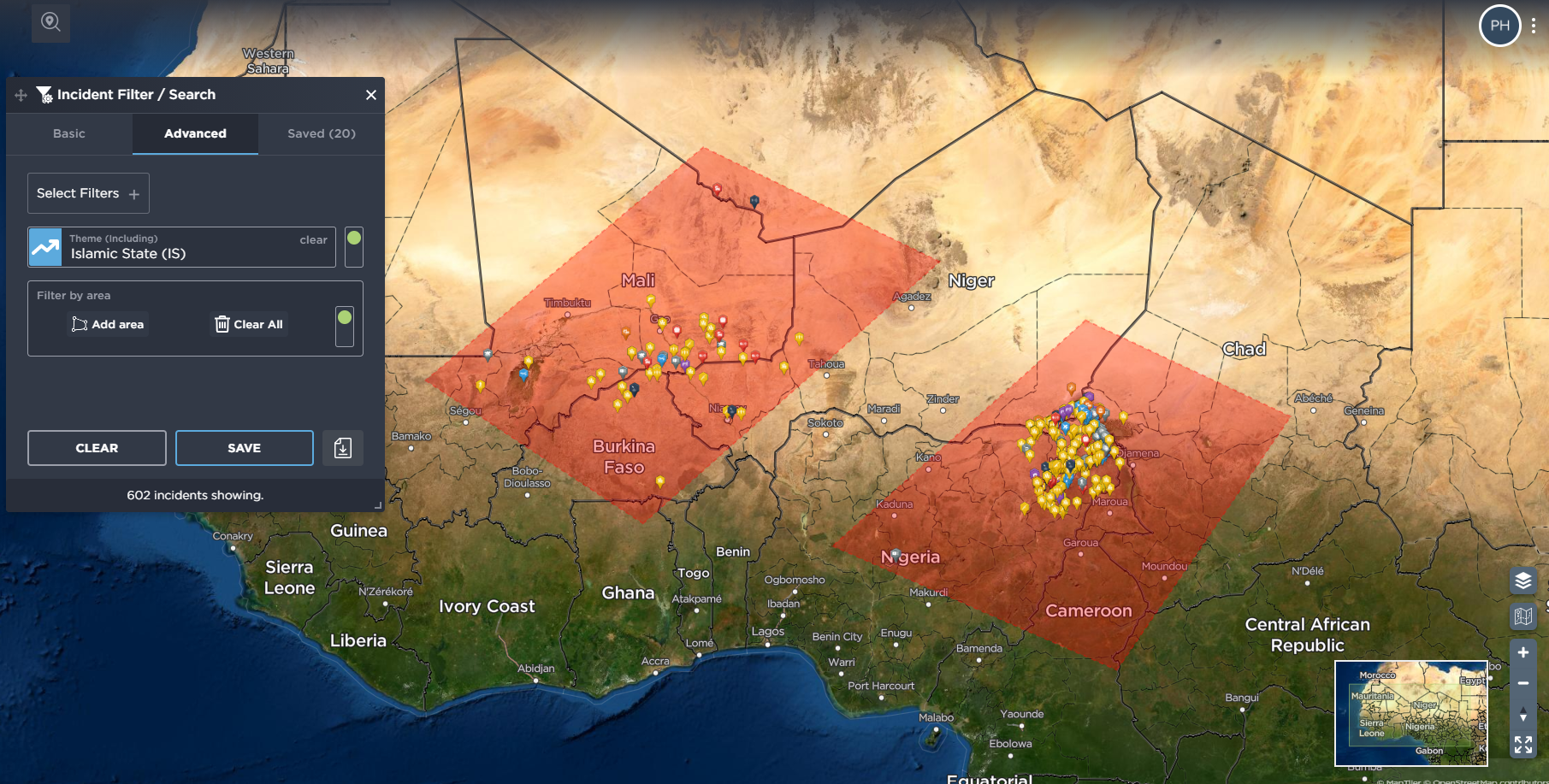

Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) is currently the strongest arm of ISIS in Africa. The group merged ISWAP with Islamic State in Greater Sahel (ISGS) in 2019, although both groups operate in different areas [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province)

Themes that directly or indirectly contributed to ISIS’s rise in Libya have also contributed to its rise in other areas of Africa. ISWAP is currently the strongest arm of ISIS in Africa. Having emerged from a split in Boko Haram, the group has now consolidated its presence in north-eastern Nigeria after the group ousted the Shekau-led JAS (Sunna Liddaawati Wal Jihad). ISIS have since released videos of former JAS fighters pledging allegiance to ISWAP. Though internal tensions are likely to remain and the group may not be the unified fighting force it presents itself as, there is clear indication that the group has been empowered. Since Shekau’s death, the group has been active in areas in which JAS was active. In northern Cameroon, for example, where Cameroonian vigilante and security forces curtailed JAS activity since the start of 2021, ISWAP have conducted several attacks on security forces in recent weeks since the death of Shekau. The group is likely to pose a considerable threat in the Diffa region of Niger as well as in Nigeria, particularly in the north west and central areas, by exploiting weak security, disillusionment, poverty and increasing communal tensions. The poor state of the Nigerian economy and growing frustration with the Buhari government could give rise to further instability which will allow ISWAP to make further territorial gains.

ISIS merged ISGS with ISWAP in 2019, though both operate in separate areas. The decision itself, however, is perhaps an indication of ISIS’s wider aspirations in the region. ISGS has been heavily active in the Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger tri-border area in recent years, although the group has had several high-ranking leaders killed by France’s Operation Barkhane force in recent months. Furthermore, competition between the group and Al Qaeda, who are the dominant group in West Africa and the Sahel region, and continued operations against the group could see its survivability tested. However, the group remains the dominant group in Niger, where it has demonstrated its capacity to carry out attacks and collect Zakat tax in a number of regions in a country whose extreme poverty rate is at 42.9%, according to the World Bank, and where political tensions remain high. Coupled with recent developments in Nigeria, ISWAP and ISGS could consolidate their presence in Niger.

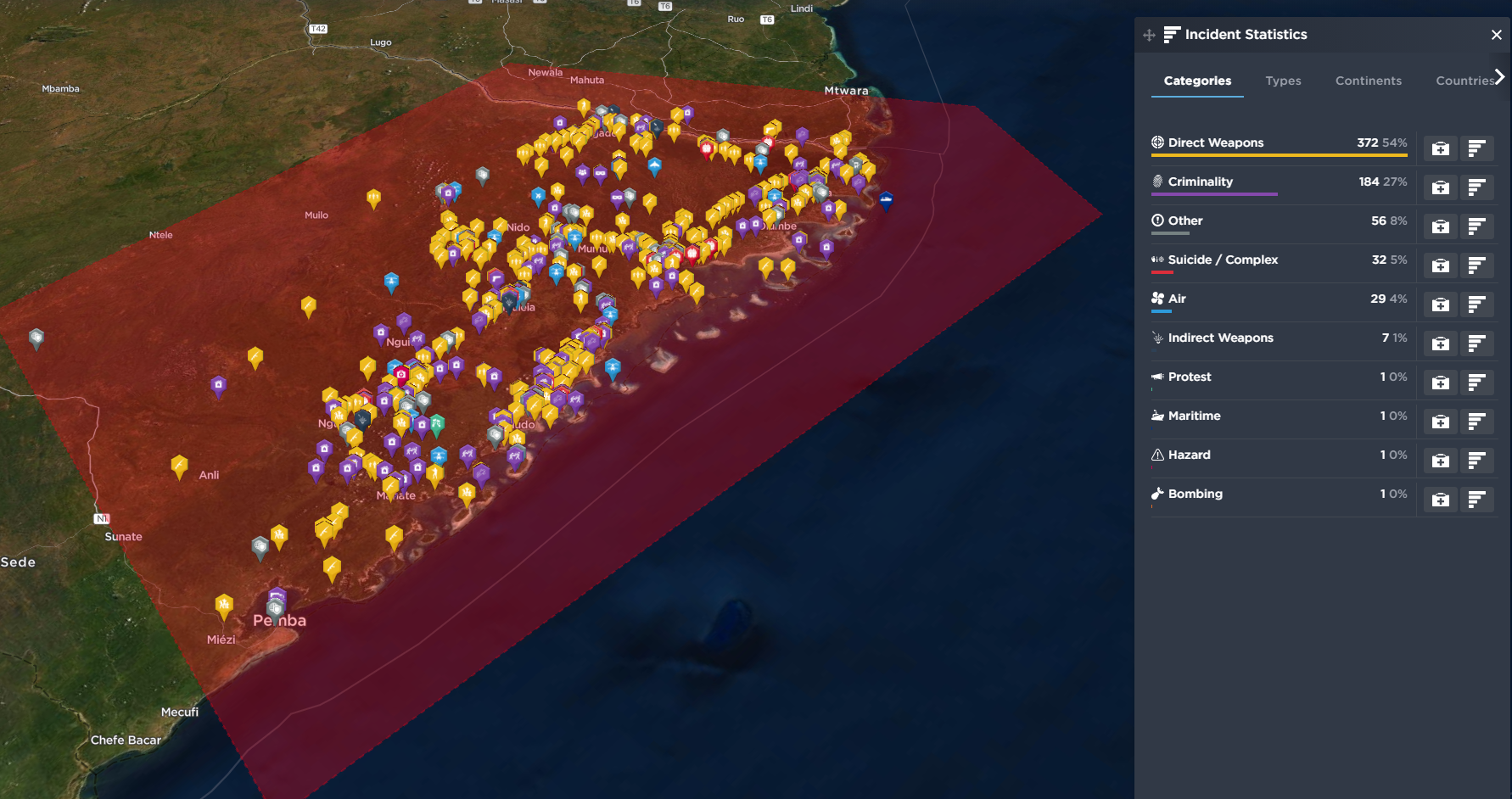

Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) consists of jihadist groups in Mozambique and Democratic Republic of Congo [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

ISCAP (Islamic State Central Africa Province)

In 2019, ISIS declared the formation of ISCAP, claiming their first attacks in the Democratic Republic of Congo and then in Mozambique. The ADF (Allied Democratic Forces), who operate in the former, and ASWJ (Ansar al-Sunna Wa Jamma), who operate in the latter, do not have the capabilities of other ISIS wilayahs in Africa, such as ISWAP, in that their attacks are not as sophisticated. However, the ADF recently carried out their first, although unsuccessful, suicide bombing in the eastern city of Beni, showing the group’s tactical evolution. ASWJ have also launched coordinated, multi-pronged attacks on towns over the last two years, demonstrating that they are also evolving. Both groups have shown resilience and mobility and will likely continue to demonstrate the latter despite recent offensives launched by local and foreign security forces.

Both groups operate in areas where there is discontent with the government and where poverty is rife, not just in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but also in neighbouring Uganda and Tanzania, giving both groups room for expansion internally and externally. ASWJ, primarily operating in the districts close to the coast in the Cabo Delgado Province, could relocate their bases further inland, possibly expanding into the Niassa Province. The group has come under pressure by government security forces backed by the RDF (Rwanda Defence Forces) in recent weeks around the LNG project near Palma, Mocimboa da Praia, Muidumbe and Nangade districts. Further pressure on the group is likely to increase with the SADC (South African Development Community), Stand-By Force, expected to begin operations imminently. Expansion into the Niassa Province or other provinces and districts in Cabo Delgado could result in the group’s ranks growing and an expansion in target selection with mining concessions in Montepuez District, of example, at risk of an attack.

ISS (Islamic State Somalia) and ISIS Sinai Province

ISS remains weak when compared to the size and strength of Al Shabaab. In 2020, USAFRICOM estimated that the group’s size is in the low hundreds range. The group predominantly operates in Puntland’s Bari region, but increased expansion into more central areas of Somalia, for example, could see them encounter resistance from Al Shabaab.

ISIS Sinai continues to be an incessant threat for Egypt with the group continuing attacks not just against Egyptian security forces but also against regional economic interests, with attacks on a gas pipeline to Israel. Given the poor socio-economic conditions and state repression in Egypt and continued post-Arab Spring instability in the wider region, ISIS Sinai, and other ISIS wilayahs including ISIS Algeria Province, could see their ranks grow with an influx of foreign fighters. Further strengthening of the group in the Sinai could also disrupt maritime traffic.

Heatmap of ISIS activity in Africa [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

The Expansion of ISIS in Africa

Major factors that combined to create the conditions for ISIS’s success in Iraq and Syria are all present in the African continent and it is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future. These local dynamics, such as poor economic conditions, political instability, communal tensions, civil war, poverty and associated marginalisation and discontent, have played an important role in the emergence of the aforementioned groups. The debilitating economic impact and political instability linked to COVID-19 and related anti-government sentiment is likely to be exploited by jihadist groups as many lose faith in existing political systems. External dynamics have also played a crucial role, such as the role of foreign fighters and the role that they have played in filling the ranks of local jihadist groups. Regional instability and porous borders have added to challenges faced in countering the threat posed by ISIS and other jihadist groups more broadly as state capacity becomes overstretched even in more stable countries.

The various ISIS factions or wilayahs across Africa have all been able to exploit these factors, which has fuelled their growth on the continent in recent years. This is particularly true of the groups operating in sub-Saharan Africa – ISWAP and ISGS in the west, and ISCAP in central Africa. While the governments of Egypt and Israel, and western powers, are unlikely to allow a group like ISIS Sinai to take root given the geostrategic significance of the province, in west and central Africa the political instability and generally less capable militaries in the region make for a much more promising situation for the group to exploit longer term. Should an ISIS-style caliphate be established in the continent it seems that these regions would be the most likely area for this to occur.

Key to countering this will be the depth and sustenance of local counter-terrorism/counter-insurgency strategies (whether they address long-standing grievances, for example), response and capacity, including any foreign support. So far, foreign interventions such as the French-led Operation Barkhane, and coalition groups like G5 Sahel, have had some limited success but have filled gaps in capabilities and capacity. Competition with other jihadist groups such as Al Qaeda may also affect the success of ISIS establishing themselves in Africa, while infighting within the different factions of ISIS could also hinder the group’s ambitions on the continent. With a planned reduction of western intervention in the region, though, the situation in this part of the continent is worth monitoring particularly closely.

We’ve written extensively about the jihadist threat in Africa and the Middle East at Intelligence Fusion. Get an in-depth insight into the insecurity in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, including Islamic extremism, in our report on the threats facing gold mining companies in the central Sahel, available to download in full here.