Illicit Mining Threatening Brazil’s Indigenous People and Ecosystem

Brazil is one of the world’s top 10 gold exporters, producing 100 tonnes of gold each year, 52 of which are illegally mined. Illegal miners known as “garimpeiros” or wildcat gold miners have ravaged the indigenous Yanomami region in Brazil leading to a humanitarian and environmental crisis. In this report we explore the scale of illegal mining in the country, the health crisis as a result of the influx of illegal miners and the potential future outcomes.

The Yanomami region spans approximately 192,000 km² and is located on both sides of the Brazil-Venezuela border. In Brazil, it is believed that over 28,000 indigenous people live in the Yanomami area, with at least 371 isolated communities. The Yanomami region is incredibly rich in natural resources – including gold.

Brazil's Gold Production and the Expansion of Illegal Mining:

To curb debt and financial issues, Brazil increased its gold production in the 1980s, which resulted in legally and illegally mined areas expanding from 31,000 to 206,000 hectares between 1985 and 2020. Brazil’s Federal Constitution prohibits illegal mining within Indigenous Lands, but this has done little to protect indigenous lands from exploitation, and illegally mined areas have expanded exponentially.

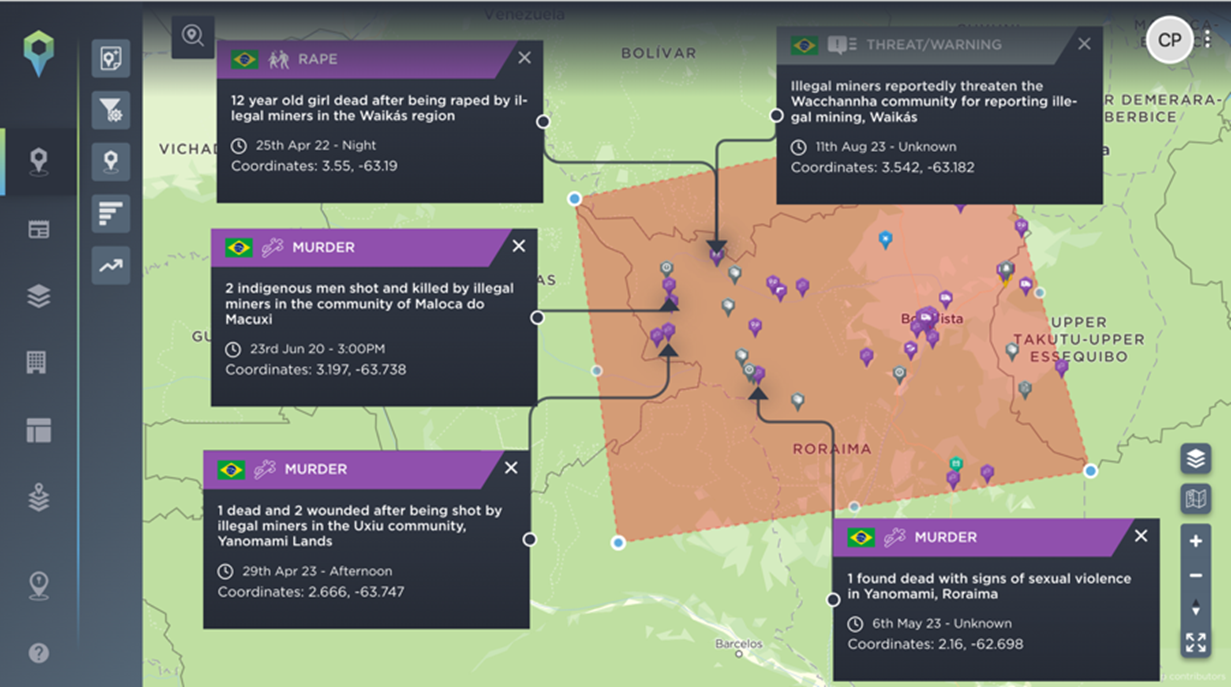

Violent incidents caused by illegal miners [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

During former President Jair Bolsonaro’s term, the situation worsened. His government changed mining codes, the designation of reserves, and the definition of artisanal mining and miners, as well as loosened mining constraints and incentivised exploration – weakening federal protection of Yanomami lands.

At the start of 2023, it is estimated that over 20,000 illegal miners were operating in the Yanomami region, causing a health and environmental crisis for Indigenous communities.

The Health Crisis:

The influx of illegal miners has brought about adverse health effects for the Yanomami people. Diseases, such as malaria, have spread exponentially, with cases rising from 2,928 in 2014 to 20,394 in 2021, primarily spread by miners to Indigenous communities.

Simultaneously, health centres have been forced to close due to violence and threats. At least seven health centres shut down, leaving the Yanomami community with limited access to medical treatment. Combined with malnutrition, this has resulted in preventable diseases becoming fatal. An investigation by Sumaúma revealed that 570 infants under the age of 5 died from preventable diseases in the last four years.

Moreover, illegal mining has worsened malnutrition and food insecurity, as mining activities drive away prey and damage the ecosystem, contaminating rivers and fish. A UNICEF study has revealed that 8/10 children under 5 are suffering from chronic malnutrition in the Auaris and Maturacá regions.

Mercury contamination has become a significant problem. Illegal miners use mercury to separate gold, which then enters river systems and contaminates the ground. This can cause serious health effects when entering the food chain: for example, foetal abnormalities or neurological and motor problems.

Illegal mining has inflicted extensive environmental degradation upon the Yanomami region. In 2022 alone, mining activities obliterated a record 125 square kilometres of the Amazon Forest. Furthermore, for every kilogram of gold mined, three kilograms of mercury are used, significantly harming local fauna, flora, and the Amazonian ecosystem.

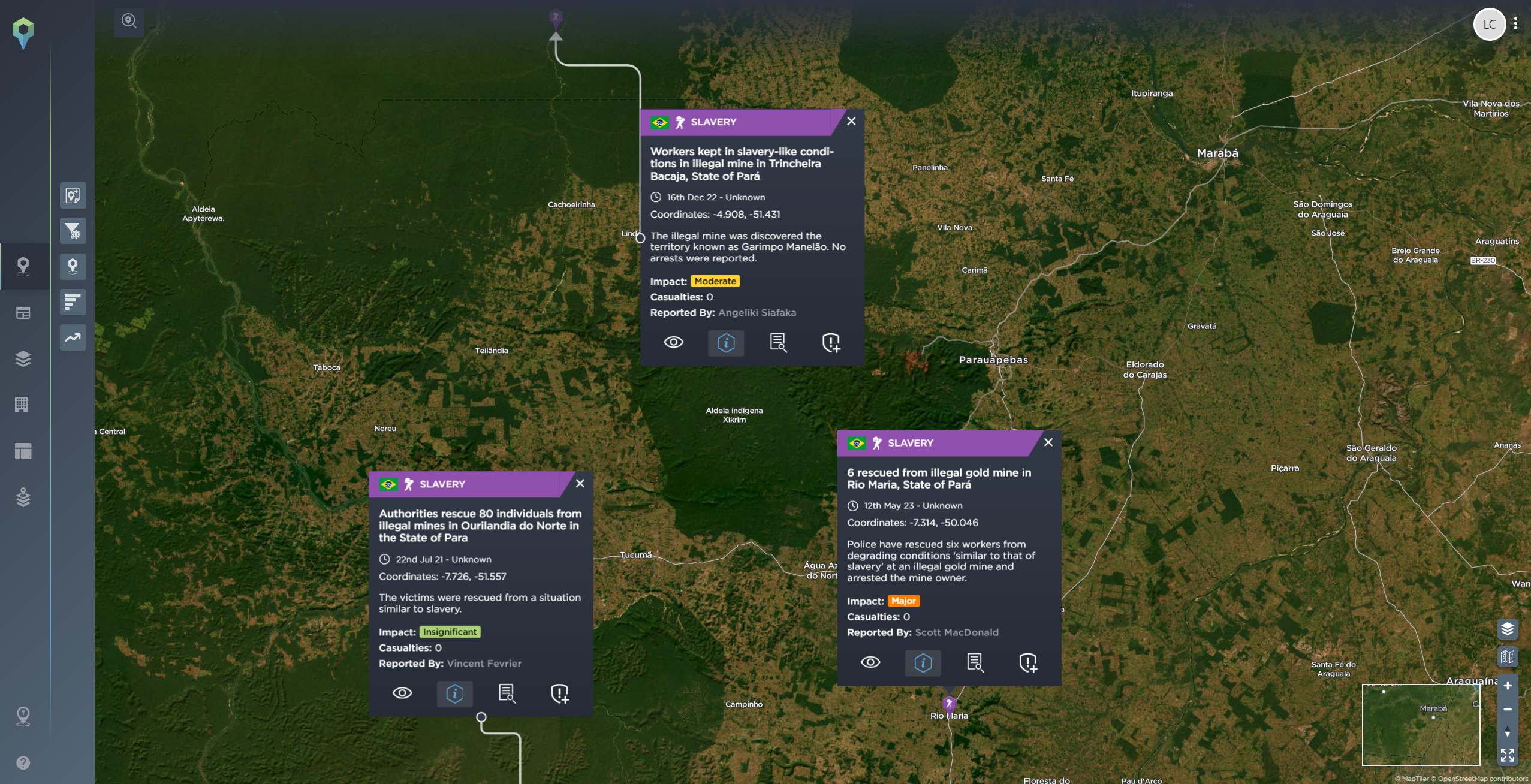

Beyond environmental impacts, the presence of illegal miners has resulted in exploitation, violence, and the disruption of social cohesion within indigenous populations. Young men are often recruited to work as miners, sometimes in conditions comparable to slavery, and are compensated with alcohol, firearms, or other incentives. This absence of men from the community has also raised safety concerns for women and girls, who may face increased risks of abuse and exploitation due to the miners’ presence.

Examples of slavery linked to illegal mining [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Operation Xapiri:

The Yanomami people and land have been deeply and degradingly affected by illegal mining. This has presented a veritable challenge and first test for Current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, whose policies marked a change.

With a focus on environmental protection and the safeguarding of indigenous people, on February 1st 2023, Operation Xapiri was launched to tackle the illegal mining problem. Taking its name from the Yanomami people’s forest guardian spirits, Operation Xapiri aims to tackle three areas: the Yanomami health crisis, stop illegal mining and halt environmental degradation in the area.

Tackling the health crisis:

The first response has been humanitarian. On the 20th of January 2023, a state of health emergency was declared in Yanomami lands. Since then, the Ministry of Health has reportedly invested over R$ 19 million to restore the health system in Yanomami lands. A comprehensive plan of emergency actions has been set out, including the following: restoring the flow and supply of medical supplies, recovering and restoring health services, recruitment and deployment of healthcare professionals from different sectors, and overall expanding the level of care in the Yanomami region. As a result of this comprehensive plan, at least seven health centres have been reopened in several key areas. Relief packages have also been flown into Yanomami lands to help curb malnutrition. In the very first week of Operation Xapiri, over 61 tonnes of food and medical supplies were flown into the area.

Disrupting illegal mining:

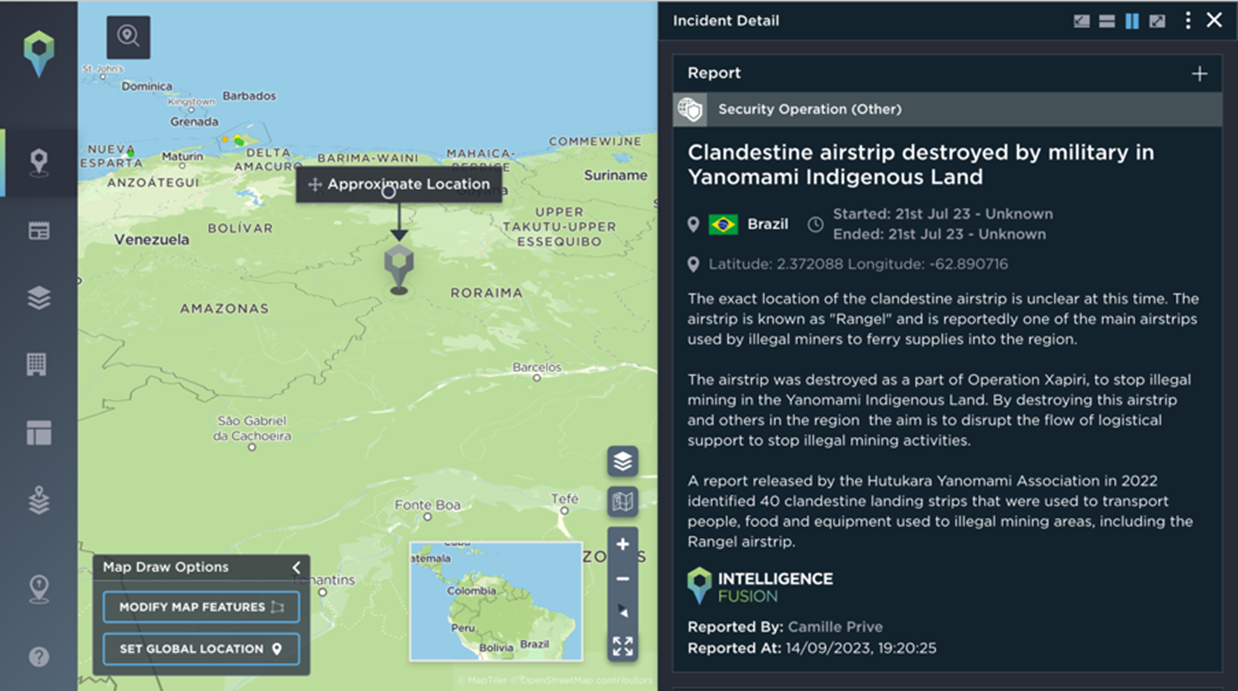

The subsequent approach of Operation Xapiri has been a military operation designed to disrupt the overall flow of supplies rather than target individual settlements to stop illegal mining and thus stop further environmental degradation. This operation has been jointly undertaken by several bodies: Ibama (Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), the Federal Police, the National Public Security Force, the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), the Armed Forces and the ministries of Justice, Indigenous Peoples and Defence.

Enforcement operations by these bodies have been targeting infrastructure and modes of transport used by the miners to disrupt their supply chains and the flow of their operations. For example, a large part of the operation will include restricting airspace and planes suspected of supplying illegal camps will be forced to land for identification and dealt with accordingly.

Clandestine airstrip destroyed by the military [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Finally, Lula’s government are also taking legislative steps to eradicate illegal gold mining. The Brazilian government are currently studying proposals to update the country’s laws targeting illegal mining. One of these proposals includes the requirement for electronic tax receipts for the buying and selling of the precious metal. The Federal Police are also investigating if previous President Jair Bolsonaro’s government could face “genocide” charges due to the crisis.

Positive Outcomes and Challenges:

In the short term, Operation Xapiri has achieved significant success. According to the Ministry of the Environment, within the first three months of the operation, 327 mining camps were dismantled. Additionally, 18 planes, one helicopter, and dozens of vessels were destroyed, and various equipment, including machinery for mineral extraction, chainsaws, mercury, satellite internet modems, cell phones, and weapons, were seized. In terms of raw materials, since the operation’s inception, authorities have confiscated 36 tonnes of cassiterite, 26,000 litres of fuel, and a small amount of gold.

The Ministry of Indigenous People has claimed that 80% of illegal gold miners have been evicted from the area. Comparing the period between February and April 2022 to the same period in 2023, there has been an 80% reduction in deforestation in areas affected by mining. Furthermore, images captured by the Brazilian armed forces demonstrated a significant reduction in water pollution in the Uraricoera River, directly attributable to decreased mining pollution.

However, the government’s long-term commitment to this operation remains uncertain, and the positive short-term effects may be short-lived. Approximately 1,500 to 2,000 illegal miners continue to resist eviction violently.

A report titled “Yamakɨ nɨ ohotaɨ xoa! – We are still suffering” criticized the government operation for its lack of coordination among different agencies. This lack of coordination has rendered the operation less effective in addressing the health crisis and evicting remaining miners from the region.

Politically, President Lula may encounter obstacles in dealing with illegal mining in the long run. Reports suggest that several senior security officers are involved with garimpeiro gangs, undermining the operation’s effectiveness. Additionally, the governor of Roraima is allegedly pro-garimpeiro and has proposed laws that would essentially make it illegal for public officials to destroy mining equipment. Some experts argue that the operation’s success in the long run may require complementary socio-economic solutions.

Furthermore, while the illegal mining crisis in Brazil appears to be subsiding, it seems to have shifted to Venezuela. The Venezuelan government is currently less equipped and inclined to deal with the problem. Images released by the Venezuelan SOS Orinoco group show the emergence of three clusters of mines a few kilometres from the Brazilian border in Venezuela following the crackdown. The SOS Orinoco’s director has warned that “the garimpeiros are coming over the border into Venezuela where they know they are going to have a safe haven and do business.” This highlights the need for regional cooperation to address the cross-border nature of illegal mining.

In conclusion, illegal mining in the Yanomami region of Brazil has caused severe harm to Indigenous communities and the environment. Operation Xapiri represents a significant step toward addressing this crisis, with positive short-term outcomes. However, long-term commitment, coordination, and socio-economic solutions are crucial for sustained success in combating illegal mining and its associated impacts on Indigenous communities and the environment.