Healthcare risk and health system sustainability in South Asia

Exploring healthcare risks and the factors threatening the sustainability of health systems in India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bangladesh

South Asia, a region with a combined population of nearly 2 billion people, is facing its worst health crisis to date.

Exhausted by the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare systems within Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and Bangladesh are close to collapse. Whilst developed countries are implementing strategies to deal with patient backlogs, and ensuring medications are widely available, developing countries are experiencing resource depletion and optimistic aims to recuperate overworked systems. This situation raises a major question; are sustainable healthcare systems in South Asia achievable?

In a nutshell there is no easy answer to this question, however mixed reports suggest that although health governance is improving, this increase is creating new risk factors. In answering the question, this blog, in brief, looks to address:

- The sustainability of healthcare systems

- Risk Factors; Sri Lanka, India, Nepal and Bangladesh

- Financial avenues

Sustainability of Health Population

Whilst studies report that a major challenge towards South Asian healthcare systems is the lack of funding allocated to health governance, it is important to consider the geo-outbreaks that contribute to an increased demand on overloaded systems and thus an increased level of healthcare risk.

Asia is home to 60% of the global disease burden of infectious diseases, notably, Tuberculosis, AIDS/HIV, Malaria and Hepatitis B, with Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) causing approximately 9 million deaths annually across South Asia alone.

The challenges of the region’s economic status are likely to be overshadowed by the cost required to allow for a robust healthcare system; resulting in inflated medication prices, a lack of finance to provide training to healthcare providers, and to maintain and build new clinics/hospitals.

Without addressing ground level faults such as exceeding hospital input, and a contingency to manage hospital supplies; the sustainability of a health system is jeopardised. A collaborative approach from funding bodies and health ministries (globally and regionally) is crucial in stabilising collapsing health systems.

Risk Factors

Lifestyles, living conditions, and lack of sanitation are amongst many of the ongoing risk factors that are generating host environments for both NCDs and communicable diseases.

Current practices, although somewhat effective, can hinder healthcare systems if policies and procedures are uncommunicated, unsafe and unaddressed. Studies suggest that rural areas suffer from a lack of access to healthcare facilities, whereas inner cities are struggling with bed sharing, and overcrowded hospitals.

The warming of the planet and adverse weather, combined with urban migration is giving rise to new, or more frequent infectious outbreaks and non-infectious diseases increasing South Asia’s global burden of disease. With a growing disease burden, short and in particular long-term health treatments, clinics and healthcare settings are becoming overwhelmed and unable to provide a sustainable care plan, often with fatal consequences.

Notably, developing countries are seeing an increase in diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, amongst other NCDs likely due to an increase in tobacco and alcohol usage, along with lifestyle, diet and physical activity changes. This increase in NCDs is adding long-term pressures on ensuring continuous and plentiful medications. A lack of internal sustainability, specifically for smaller regions, creates vulnerabilities to population welfare, and encourages greater need for funding avenues to be explored.

Sri Lanka

Continuous development of the state funded healthcare system in Sri Lanka has led to improved emergency care and the elimination of mother to child transmission of Syphilis and HIV/AIDS, along with Malaria and Measles. The creation of an effective surveillance system to track/monitor infectious diseases along with introducing immunisation campaigns has led to a great decline in infectious diseases nationwide. In achieving medical advances, Sri Lanka is also regarded as the region with the lowest maternal mortality within South Asia.

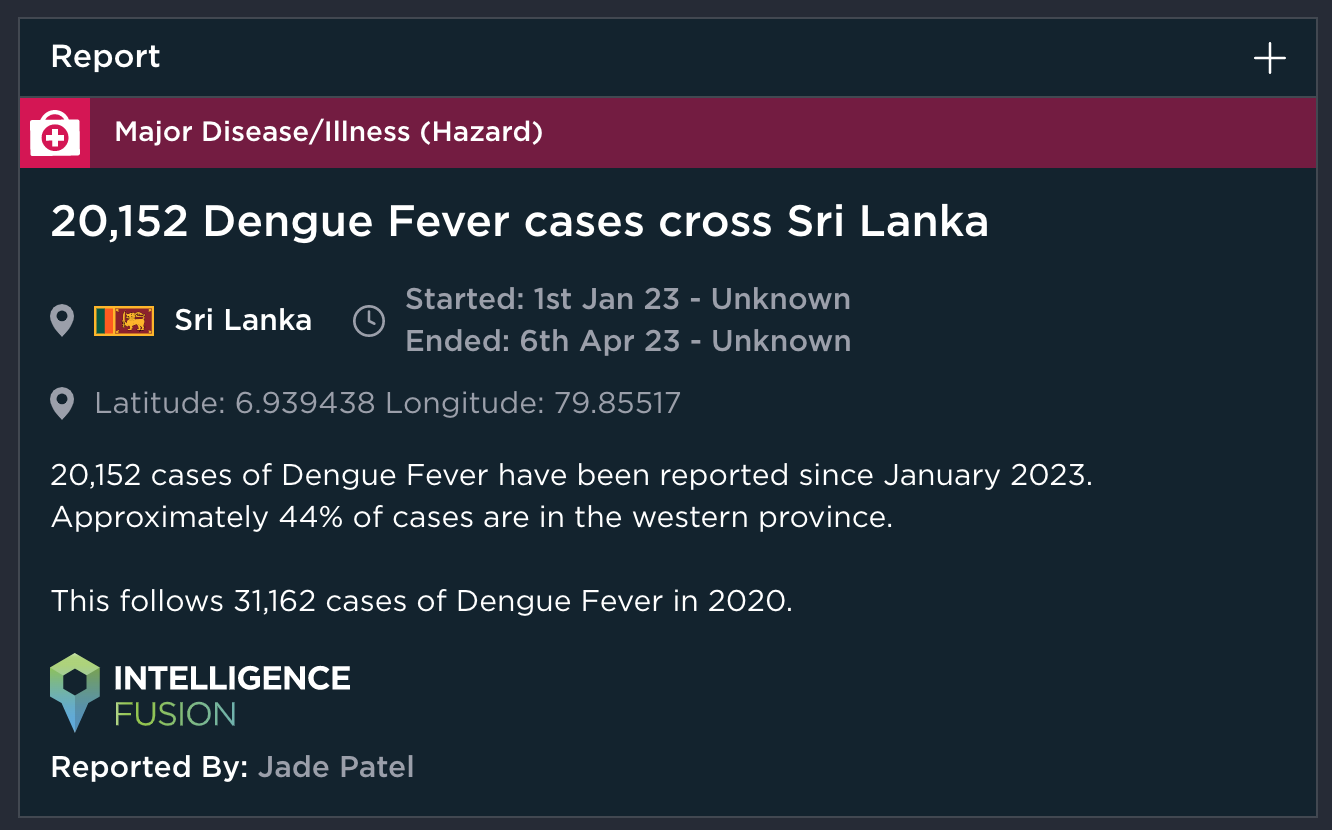

However, healthcare risks remain, and Dengue Fever remains one of the main infectious drivers across the island, along with an increase in NCDs, notably cancer, stroke, diabetes and cardiovascular disease; accounting for nearly 90% of the disease burden in Sri Lanka. Food insecurity combined with malnutrition is also increasing undernutrition related illnesses (diarrhoeal) and obesity.

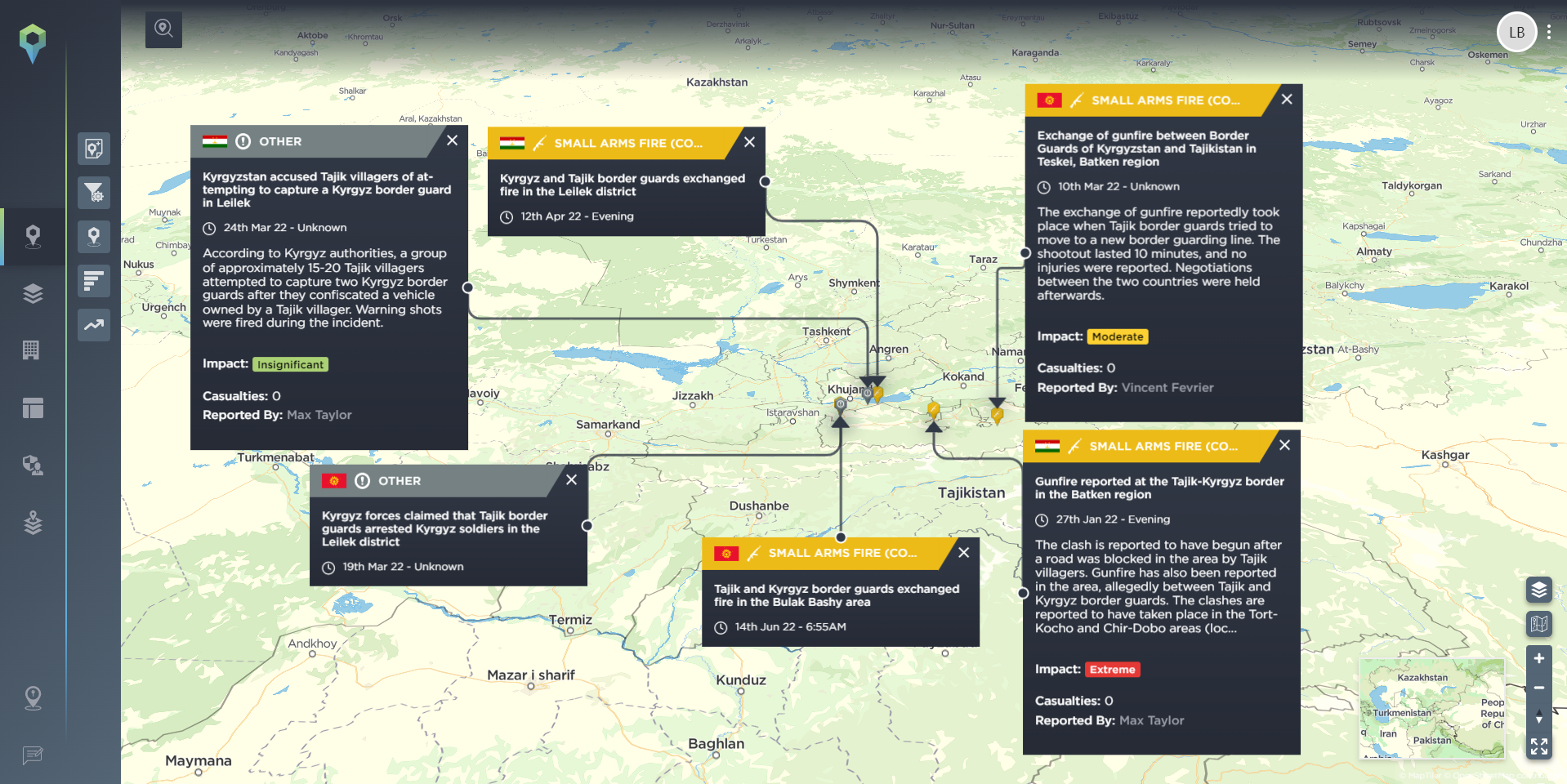

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Despite effective advances, there remains a shortage of trained specialists with a notable migration of trained staff working in urban hospitals, leaving rural clinics understaffed. This is likely due to better working conditions including safety, wages and travel.

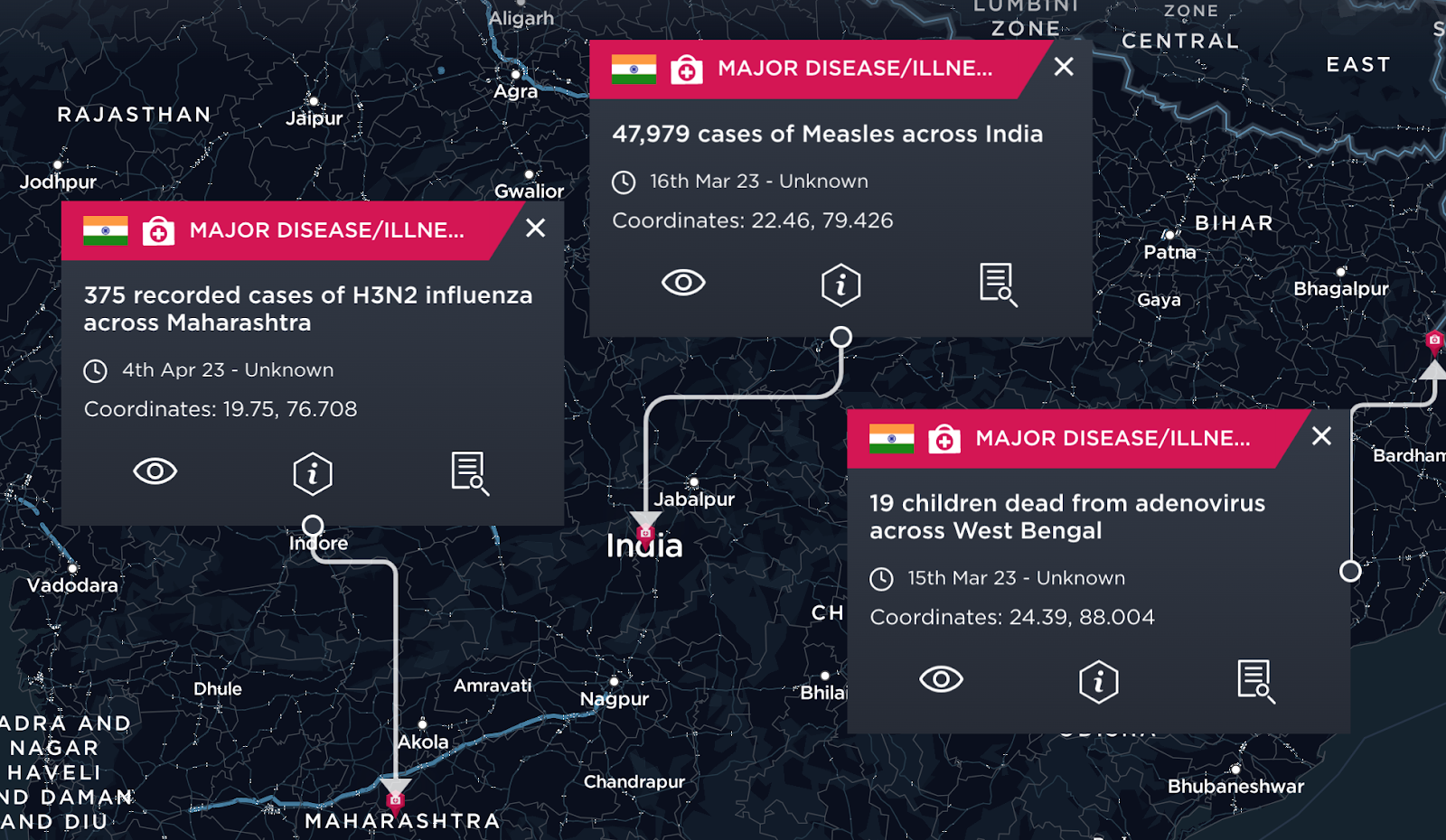

Despite past bulk medication purchases by the State of Pharmaceutical Cooperation, Sri Lanka hit a medication crisis in 2022 and 2023, resulting in thousands of routine antibiotics, steroids and family planning tablets becoming outdated and being discarded. The lack of medications to treat even low-risk illnesses creates the risk of pathogens becoming more deadly, specifically if left untreated.

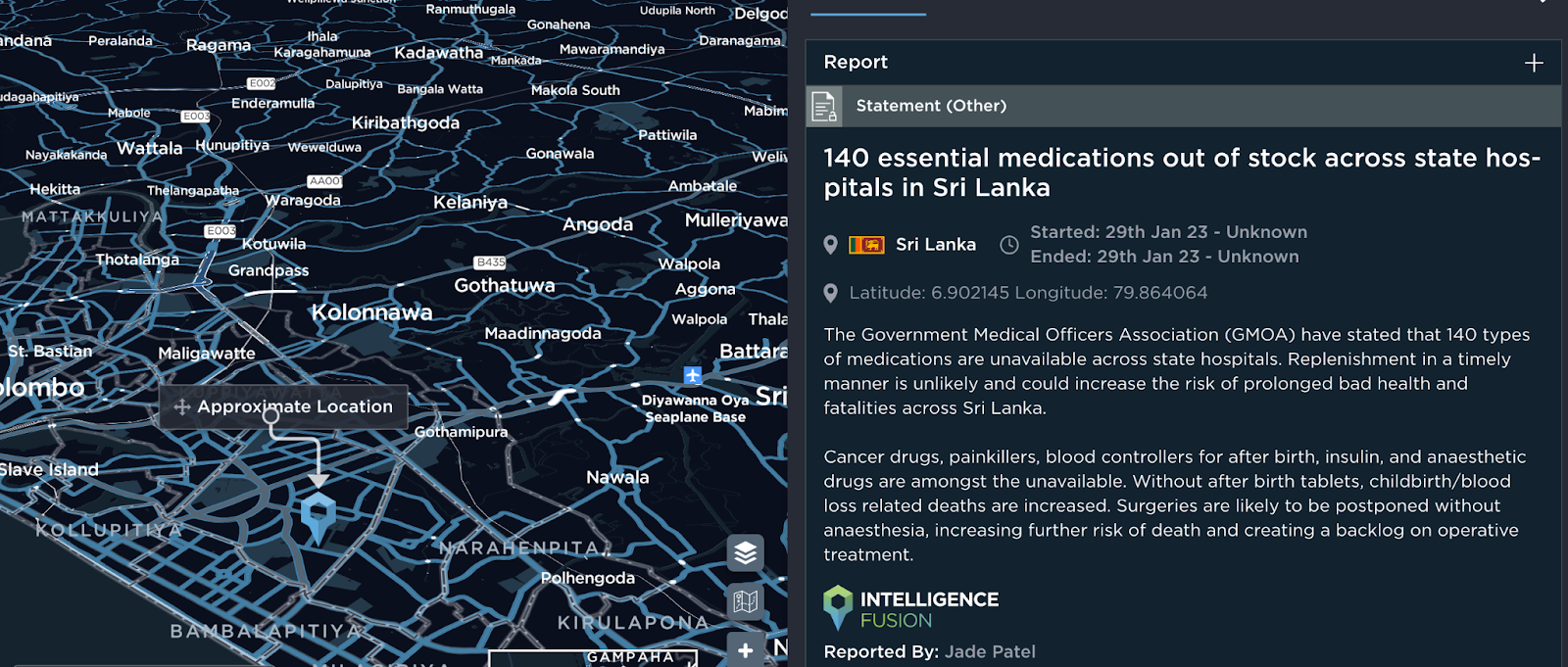

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

India

Underfunded and understaffed healthcare systems are decreasing the sustainability of India’s healthcare system. Reports dating back through the early 2000’s, suggest issues relate to the inclusivity of the healthcare offered to residents. With India contributing 2% of its GDP to public healthcare, revisions such as making emergency treatment mandatory in public and private hospitals under the reimbursement of the government are proving unrealistic with immense backlash.

Aside from funding, a study showed that other prime causal factors are likely due to the lack of awareness and education on basic healthcare and/or where to receive it. Another consideration, specifically in lower educated areas, is health is considered a low priority, likely creating reluctance to seek medical aid. Issues have also arisen on the reliability of lower-socioeconomic or rural settlers being able to access timely, affordable and long-term health treatments.

With multiple concurrent health outbreaks, COVID-19 created an unanticipated breaking point for the country’s health system. In 2021, India exhausted vaccination mandates, resulting in temporary suspension of manufacturing for a series of vaccinations.

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

In the aftermath, the nation is experiencing overworked health workers, lack of medical resources and overcrowded, unsanitary hospital environments. New initiatives such as Government and private hospital bed allocation are in the pipeline to make a small step in improving patient healthcare and reducing healthcare risk factors.

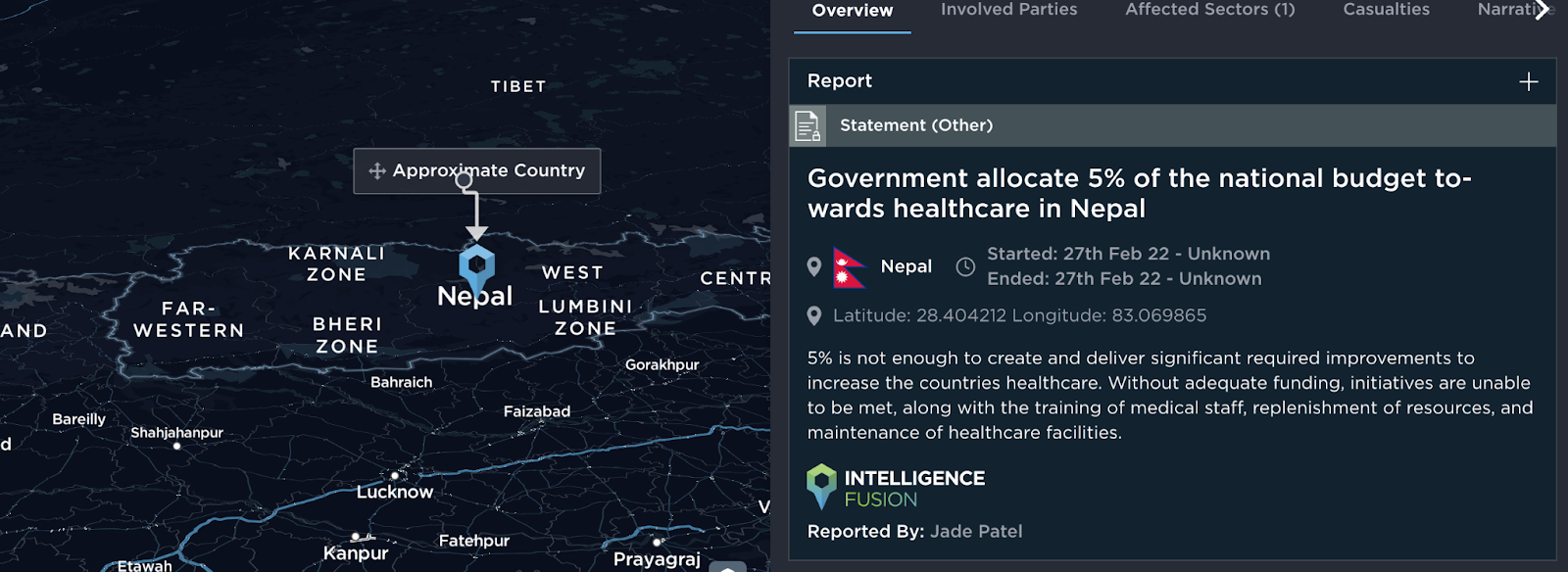

Nepal

Reliant on both public and private sectors, the healthcare system is ‘regarded as failing to meet international standards’, despite having the second-highest life expectancy in South Asia, partially due to a decrease in birth rate mortality.

Scholarly articles, combined with extensive research suggest that Nepal has the highest prevalence of disease in rural areas compared to neighbouring regions due to lack of access to healthcare. A study showed that only ‘61.8% have access to healthcare facilities within a 30-minute radius’.

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

As a remedial action, the Government created the Social Health Security Development Committee, aimed at providing healthcare to secluded and low socioeconomic areas. However, financial burdens, amongst government corruption is hindering the committee’s initiatives.

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Whilst the assurance of a better system is reliant on finance, community-based health insurance schemes have also proved to be less effective than anticipated.

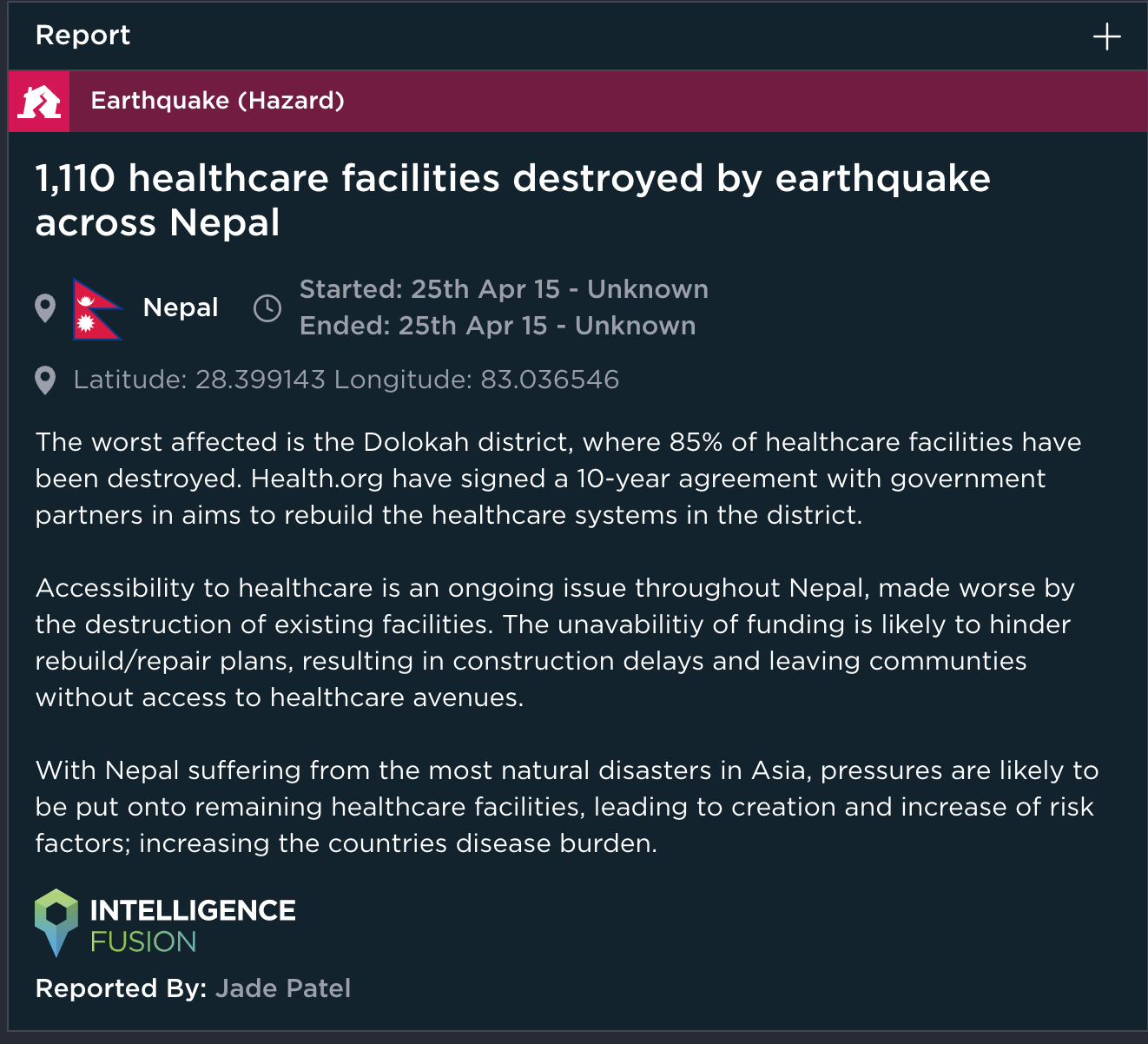

Other reports suggest a fundamental challenge is the absence of medical staff with ‘0.67 doctors and nurses per 1,000 people’, and the prevalence of natural disasters such as severe earthquakes, flooding and landslides (see below image).

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

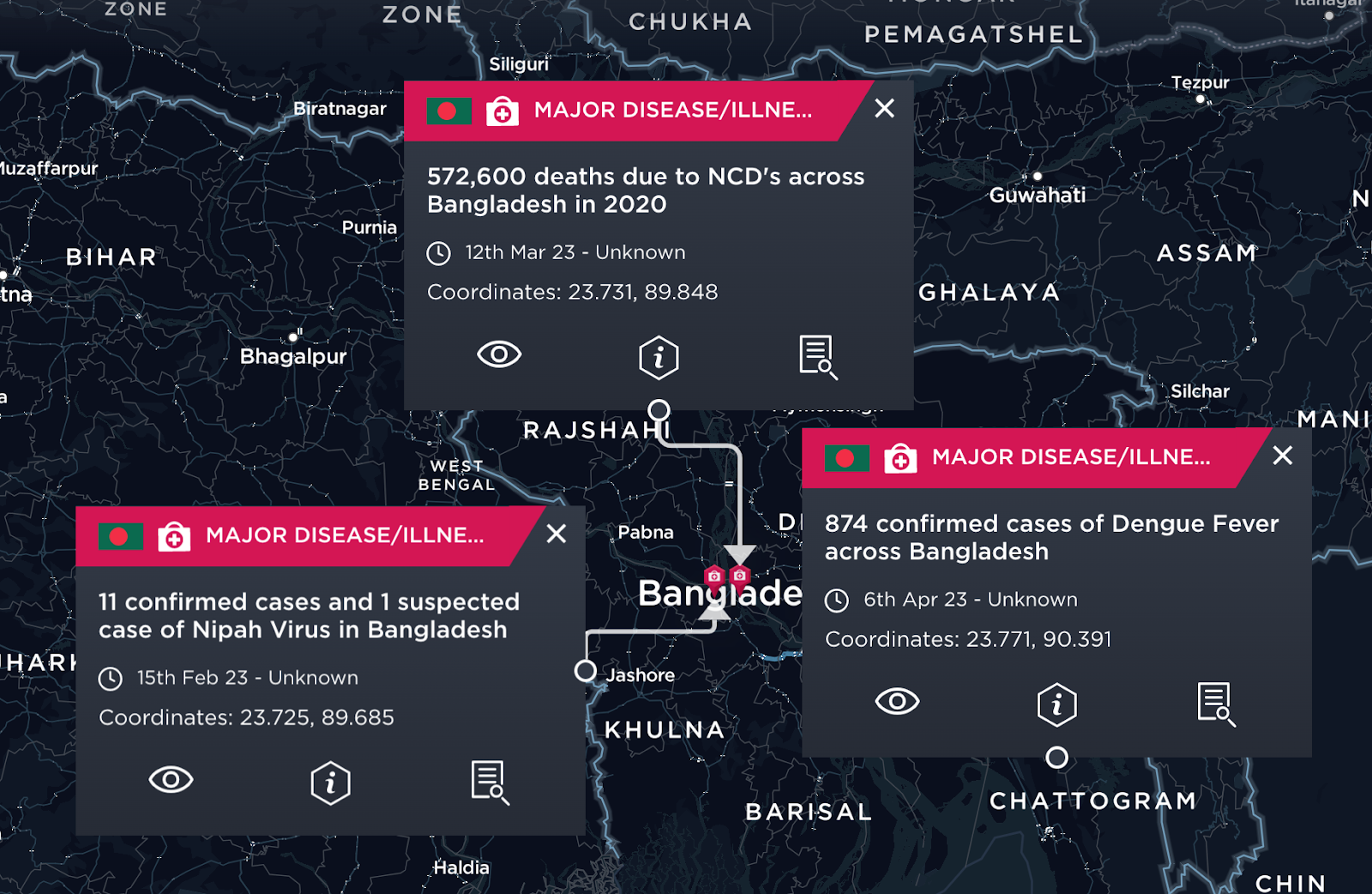

Bangladesh

After a number of reforms, Bangladesh has achieved impressive gains in improving treatments, including meeting the Sustainable Millennium Development Goal 4; reducing child mortality. However, despite efforts to increase health sustainability in Bangladesh it is still facing several health system challenges, including a large refugee population in need of medical aid, and a continuous outbreak of Dengue Fever over multiple cities.

[image source: Intelligence Fusion]

In a paper published by the World Health Organisation four key areas of improvement were highlighted; the first being the lack of communication between health care services in rural and urban areas. Without a channel of effective communication, this is likely to increase misuse of medications, as well as disallow for a sustainable resource plan. The second challenge is the shortage of trained health providers, meaning that gaps in knowledge are likely to decrease the safety and effectiveness of treatments. The third is the allocation of the government budget towards the health sector which is resulting in medications becoming unaffordable. The last highlighted challenge is access to healthcare services in urban and rural areas, with consideration to funding. Without addressing these four objectives, the health coverage throughout the country is likely to continue declining, while healthcare risk factors increase.

Financial Avenues

The World Bank has spent over USD 31 billion throughout South Asia since March 2022 in support of improving health emergency practices, along with USD 2.6 billion allocated over 10 projects that helped over 857 million people from lower socioeconomic families to purchase medication supplies. USD 2.5 billion is being used to help build and equip more than 23,000 hospitals across the regions, including healthcare centres.

With reliance on intercountry support, China, amongst other countries, have been key contributors to foreign medical aid throughout the regions, with the pandemic enabling China to express interest in global health governance as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. A loan of USD 500 million to Sri Lanka, and a team of medical experts sent to Bangladesh to help boost health education and training quality are amongst a few examples.

Insurance and other financial medical support is likely challenging in South Asia due to economic pressures spread over other sectors outside of health. With consideration to tax and GDP, countries are unable to allocate sufficient funds to tackle healthcare issues to a sustainable and contingent level. Risk pooling, prepayments and user fees are likely to alleviate financial burdens for the respective government. Whilst user fees are a barrier to healthcare for low income countries, they have a polar effect on increasing service delivery, medication stock renewal and payments such as salaries and bills.

Aside from global and regional health policies to aid developing countries, modern research, private and NGO funds are heavily relied upon across South Asian regions to increase funding avenues and health governance.

To conclude, whilst improving education, training, affordability and accessibility are all key roles in building a robust sustainable healthcare system, they are not without the burden of being timely and costly. It is unlikely that sustainable health governance can be created without causing a greater financial burden for the regions. Whether this be through debt, grants or aid, the level of disease burden in conjunction with healthcare development is outweighed.

Strengthening health-industry partnerships and increasing global healthcare financial investments are a likely step in achieving a more sustainable healthcare system. Increasing accessibility and communication between all three levels; legislative, administrative and personal, is likely to increase the safety of healthcare practices along with creating better efficiency and understanding about healthcare.

Healthcare risks factor among our global intelligence coverage, with disease outbreaks included in the 159 different incident types we report – divided into 11 different categories – allowing our users to get extremely granular when filtering the more than 900,000 historic incidents on our threat intelligence platform, with nearly 20,000 new incidents reported every month.

To get more information on our data, how we report it, and how it helps the operations of some of the biggest and complex organisations in the world, speak to a member of our team today.