Afghanistan Situation Update: Terrorism, Insurgency and Crime in Afghanistan

Just under two years have passed since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, and while the situation in Afghanistan has potentially fallen out of the Western news cycle since the immediate aftermath of the withdrawal of Western forces from the country, insecurity remains a key issue in Afghanistan under Taliban rule. We provide an update on the current situation in Afghanistan from a security perspective, covering terrorism, insurgency and anti-Taliban resistance, and crime in Afghanistan.

As can be expected, Afghanistan has gone through a period of substantial change since the fall of the government and the seizure of the country by the Taliban in 2021. The Taliban once again find themselves responsible for governing the country and providing basic services to a country whose infrastructure has been extensively damaged from years of fighting. Non government organisations (NGOs) have to some degree been able to support Afghanistan’s population, but the Taliban’s hardline policies on issues such as education have come to dominate the Taliban’s perception in the eyes of foreign audiences, complicating the delivery of vital aid.

Figure 1: Image shows incidents recorded in Afghanistan in 2023 to date.

From a security perspective, it is important to note that the end of formal fighting between the government and the Taliban may have reduced the number of conflict related incidents recorded each month, but this does not necessarily represent a significant improvement in security. Instead, fighting has continued involving groups such as anti-Taliban forces and Islamic State – Khorasan Province (IS-KP,) leading to regular clashes in certain rural areas and terror attacks in population centres.

NRF activity and anti-Taliban resistance in Afghanistan

The National Resistance Front (NRF) formed shortly after the collapse of the Afghan government and saw soldiers from the Afghan security forces joining in relatively large numbers. The NRF has largely formed along ethnic lines, with fighters being recruited mostly from minority ethnic groups such as Tajiks, Panjshiris and Uzbeks. The names of many of the commanders involved will also be familiar to those who have monitored Afghanistan for some time, with key figures such as Ahmad Massoud (son of the well known Afghan commander, Ahmad Shah Massoud) and Amrulleh Saleh, former vice president of Afghanistan.

The NRF operates as a collection of militias, bound together by their opposition to the Taliban, brought together under the banner of the NRF. Whilst details regarding the structure of the NRF are relatively vague, it can be assumed that local level commanders work in relative coordination with each other, but many of the commanders are under their own individual pressures such as allowing fighters to return home, thus limiting their ability to carry out large scale sustained operations. The NRF has also received minimal support from abroad, meaning the group lacks heavy weapons.

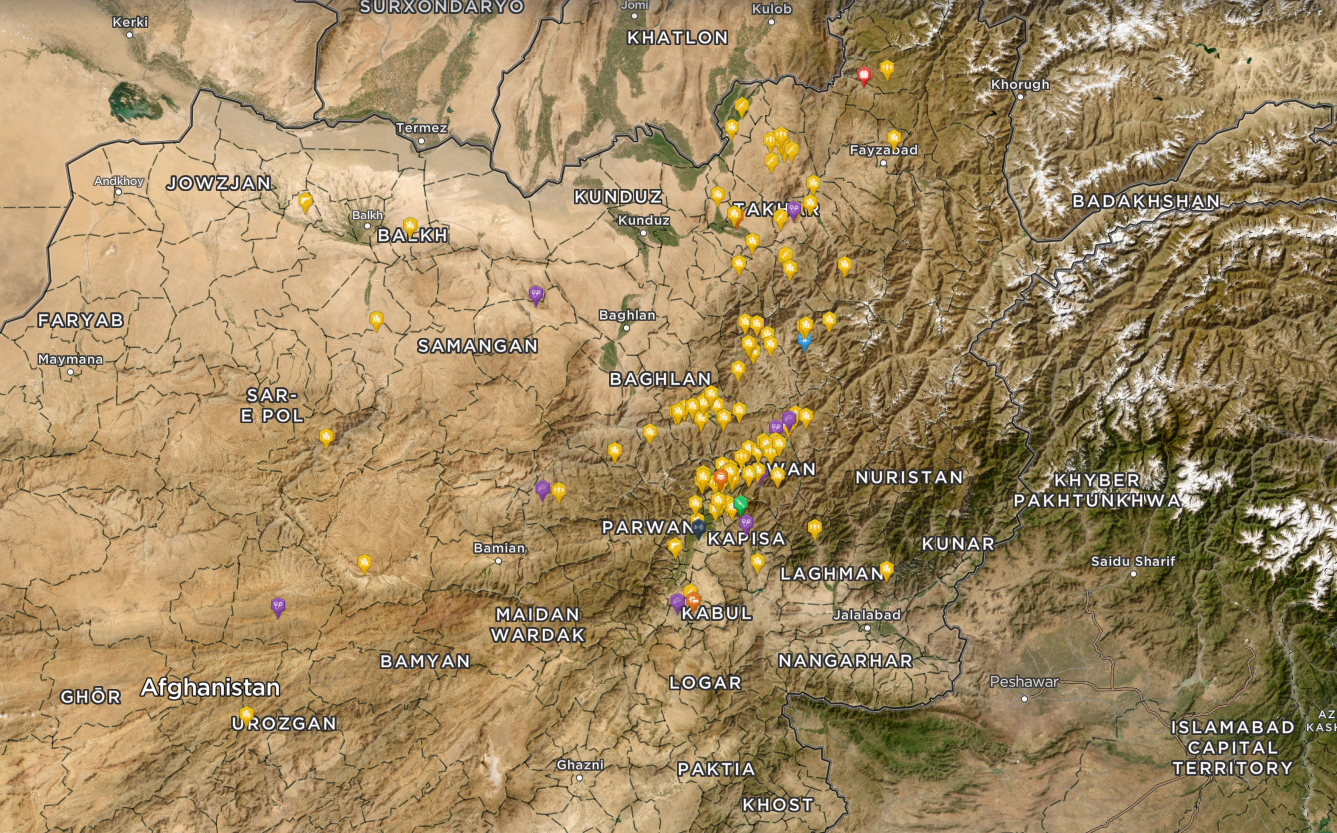

Figure 2: Image shows NRF related incidents in Afghanistan since the Taliban captured Afghanistan in August 2021. Note the concentration of incidents in Panjshir, Parwan, Baghland and Takhar.

The geographical spread of incidents involving the NRF on the Intelligence Fusion platform highlight that the group operates largely in mountainous areas in provinces with substantial ethnic minorities (such as Baghlan, Panjshir and Badakhshan). The Panjshir Valley is reported to sustain highest levels of NRF activity, and Taliban attempts to expand their own influence here have typically met heavy resistance. As has been a common theme in Afghanistan’s modern military history, the mountainous terrain has also helped offset the NRF’s material disadvantage in terms of heavy weapons.

Analysis surrounding the NRF suggests that the group’s prospects in the future are difficult. The Taliban’s superiority in numbers and weapons is not expected to change without the NRF receiving international support, and western policy makers in particular are reluctant to become engaged in Afghanistan once again. However, as mentioned already, the NRF operates in rugged territory which has proven in the past to be notoriously difficult to extend centralised power over. With this in mind, the NRF may push for a situation in which they are granted a high level of autonomy from the central Taliban government. This potential agreement would perhaps be best viewed as a ceasefire agreement though, rather than formal governance.

IS-KP activity and terrorism in Afghanistan

Counter-terrorism and the Taliban’s ability to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a base for international terror groups was a core issue during negotiations at the time of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Whilst the Taliban did agree to certain vague conditions laid out, little was known about what the Taliban would do to counter terror groups in Afghanistan, and how they would do it.

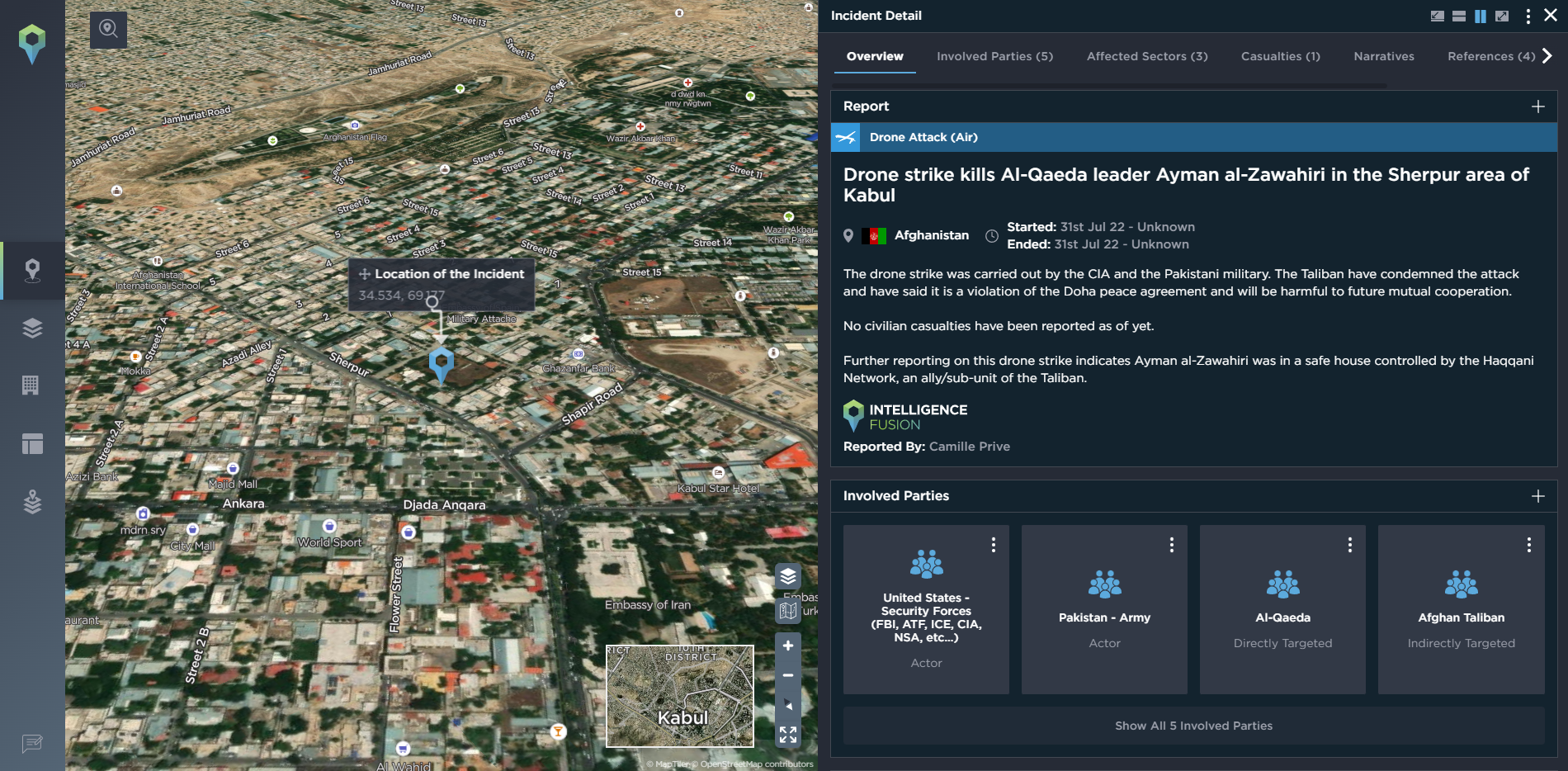

The Taliban’s historical relationship with Al Qaeda and other militant groups operating in Pakistan such as the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) almost guaranteed that any measures aimed at countering the presence of these groups would be limited to token gestures at best. A US drone strike in September 2022 which killed Al Qaeda’s leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri highlighted not only the group’s presence in Taliban controlled-Afghanistan, but also Al Qaeda’s confidence in their own safety in that they were residing in Kabul at the time of the incident.

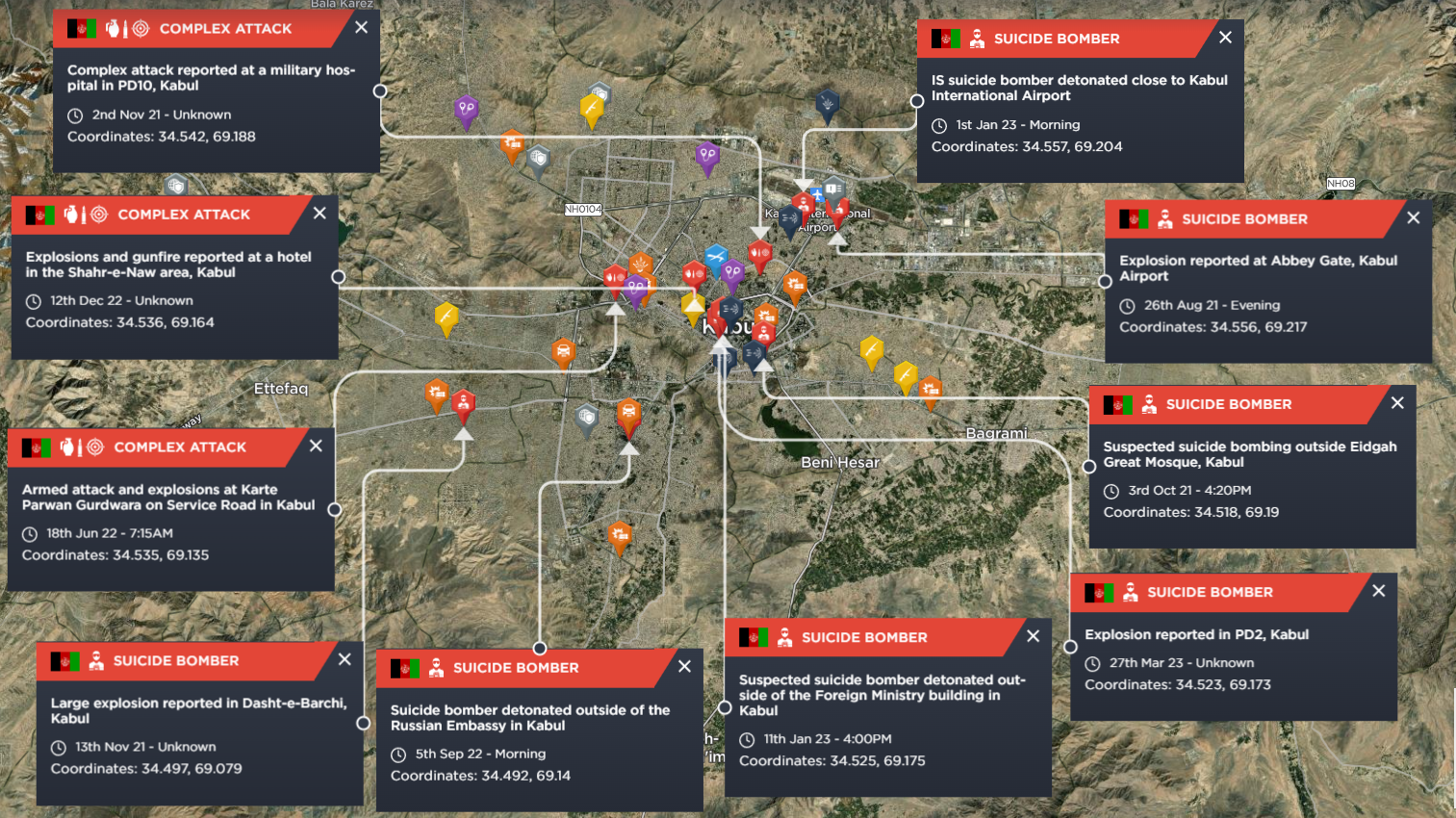

Unlike the relationship between the Taliban and Al Qaeda, the Taliban’s relationship with IS-KP has been openly hostile for years. Before the collapse of the Afghan government, Taliban fighters actively engaged in fighting with both security forces and IS-KP militants, particularly in Afghanistan’s East. Since the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban, the Taliban have been able to focus their efforts on tackling IS-KP cells and IS-KP influence, though their success in this regard appears to have been limited. Towards the end of the era of the US-backed Afghan government, IS-KP began to focus less on holding physical territory in Afghanistan, and more on carrying out attacks in population centres, particularly Kabul.

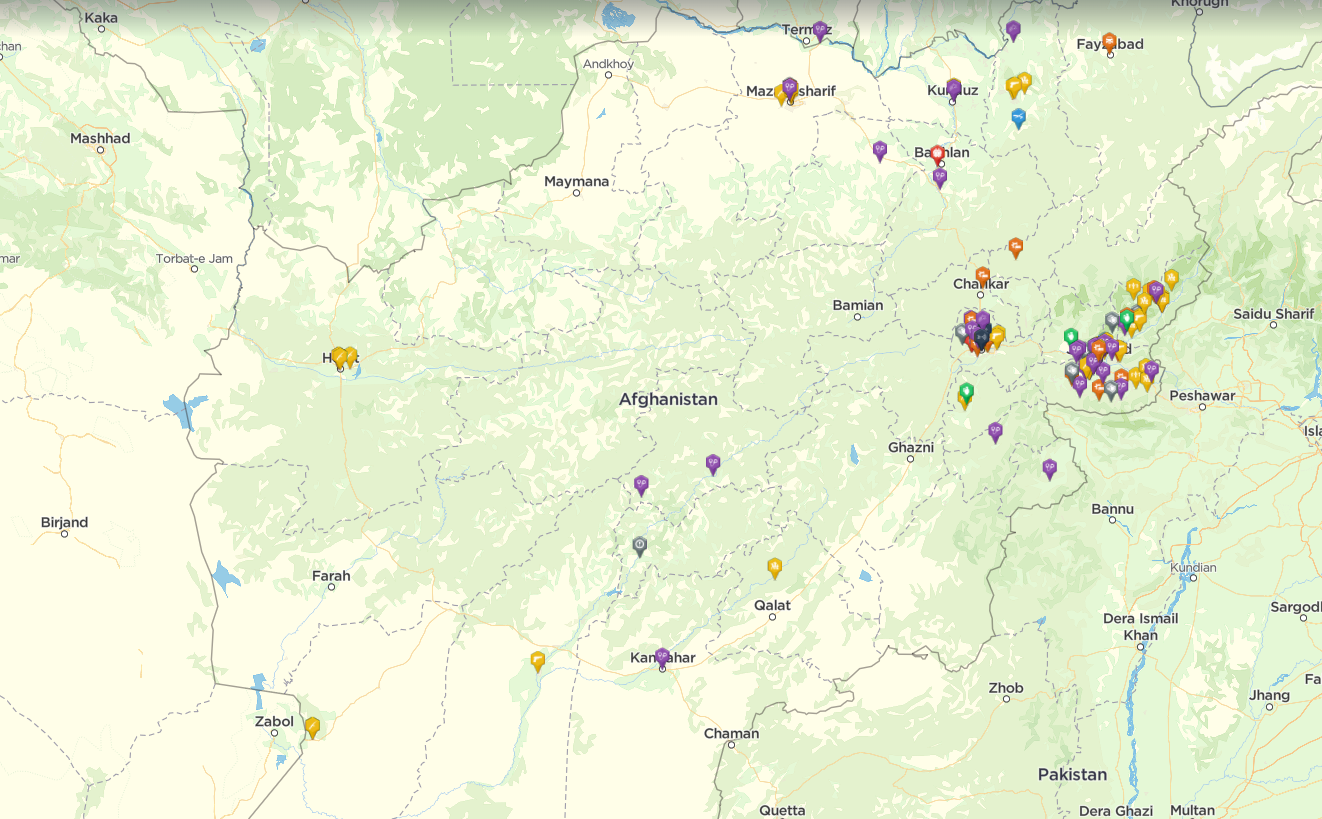

Figure 3: Image shows Islamic State - Khorasan Province activity in Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover in August 2021.

Figure 4: Suicide bombings carried out by Islamic State in Kabul since August 2021.

As a result, the Taliban have struggled to counter the presence of IS-KP in Kabul and elsewhere in the country. In the east of Afghanistan, several reports have suggested that the Taliban have taken a heavy handed approach to countering IS-KP, alienating communities such as the Salafist community. In the north of the country, rather than seeing their influence wane in the face of Taliban counter terror initiatives, IS-KP has been able to expand. IS-KP has notably focused heavily on recruitment from ethnic minorities in Afghanistan, seemingly in response to accusations of the Taliban enforcing a Pashtun-centric government. As a result, IS-KP has found recruits in the northern areas of Afghanistan, using fighters to carry out attacks in cities in the home regions.

Crime in Afghanistan

Crime is often overlooked in Afghanistan, partly due to the military situation in the country but also due to inconsistent reporting on local level crime. As a result, the volume of crime data in Afghanistan is low, but consistent reporting of criminal incidents in Afghanistan over a prolonged period of time has highlighted several trends.

Firstly, the Taliban have enforced their own distinctive legal system, with reports of public floggings and executions surfacing shortly after the Taliban seized control of the country. Particularly in rural areas, local Taliban commanders appear to have a significant degree of autonomy in how justice is delivered, and whilst this can potentially provide the Taliban with a more effective way of responding to disputes, this system is also open to corruption. Taliban commanders themselves are frequently accused of being involved in land disputes and in criminal incidents such as abductions and murder. From the perspective of an outsider looking in, it is difficult to gauge what impact the Taliban’s style of justice has had on crime rates and just as importantly, how this hardline justice is perceived by locals.

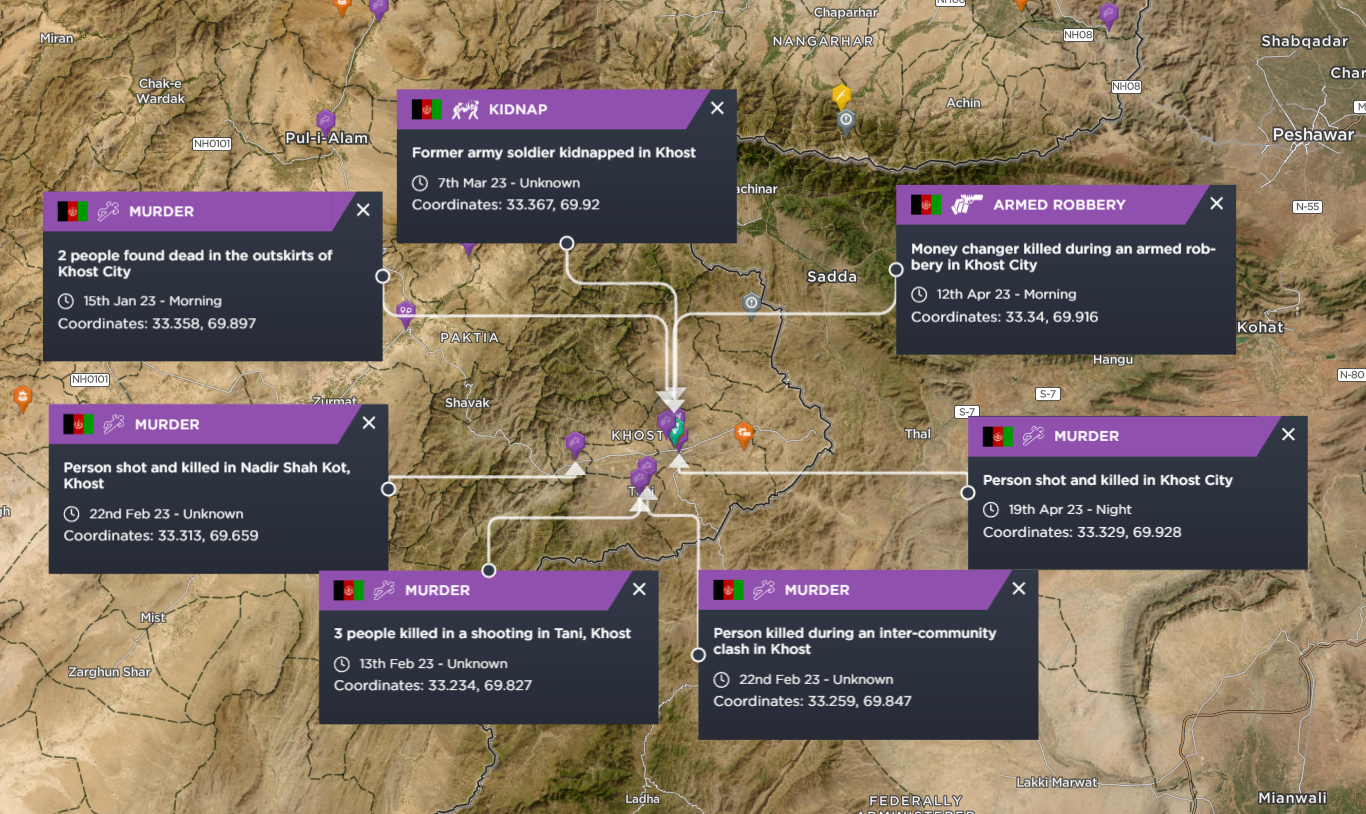

Figure 5: Image provides an example of crime reported in rural areas, outside of Kabul.

Regardless, criminal incidents are regularly reported in Afghanistan, despite the inconsistency of crime data from Afghanistan. Kabul, for example, reports multiple violent incidents including armed robberies, murder and frequent abductions or kidnappings. Taliban-linked social media publishes regular images of detained suspects (much like their Afghan government predecessors did on their own media,) but anecdotal reporting suggests that violent crime rates in Kabul are high.

Figure 6: Image shows an example of significant criminal incidents in Kabul.

Anti-Taliban media regularly reports murders and arbitrary detentions of former government employees and former members of the Afghan security forces. In many cases, after being detained by unidentified individuals, the bodies of the victims are then found days later, with local Taliban fighters often accused of carrying out the killings.

What to expect in Afghanistan?

The NRF has maintained its presence in remote areas of central and northern Afghanistan, defending key valleys from Taliban fighters. As expected, fighting slowed during winter months, but spring months have seen a slight rise in incidents related to the NRF. This rise is expected to continue into the summer months in the form of skirmishes and ambushes at Taliban positions, but without external support, the NRF is outnumbered and outgunned by the Taliban and will struggle to escalate their operations to larger scale operations against the Taliban.

IS-KP activity and influence will likely continue to spread in Afghanistan in both short and long term. The group’s strategy currently involves carrying out suicide attacks in Afghanistan’s population centres, often targeting religious sites and civilian targets such as hotels. IS-KP has moved away from seeking to maintain territory and this is not expected to be a strategic goal for the group in the short term, though a sharp drop in security in Afghanistan may allow an opportunity for IS-KP to consolidate territory in the long term. IS-KP’s presence in Afghanistan and previous attacks against Afghanistan’s neighbours may force neighbouring states to take more proactive stances regarding their border security, potentially straining relations with the Taliban.

Lastly, crime and insecurity in Afghanistan has been high since the Taliban takeover, with regular reports of murders and abductions seen in both Kabul and in rural areas. Combined with other issues such as poor provision of aid to Afghanistan, corruption among Taliban officials and poverty, high crime and insecurity rates will undermine Taliban legitimacy in the future. The Taliban has attempted to attract international partners in order to secure investment in infrastructure, energy and mining in Afghanistan, but these projects have been slow to materialise and are continually hamstrung by concerns over security.

Our analysis is supported by data from our real-time threat intelligence platform, populated 24/7 by our team of intelligence analysts. Our rich database of current and historical incidents dates back to 2015, with nearly 1 million incidents mapped and searchable using granular filtering capabilities. If you’d like to learn more about how you and your team can utilise our platform to support your organisation’s needs, book some time to speak to a member of the team now.