Will Ukraine join NATO? Analysing proposals to protect Ukraine from future aggression

How realistic are proposals to provide security assurances to Ukraine? And how likely is it that Ukraine will be successful in its accelerated attempts to join NATO?

The Russia-Ukraine war appears to be turning into a protracted conflict, and the political and economic war between the West and Russia sees sanctions and counter-sanctions continue to be exchanged, including threatening the energy supply to Europe ahead of the coming winter. However, while these events have understandably dominated coverage of the Ukraine war, attempts have been made to provide legislative solutions to Ukraine’s long-term security that are worth analysing.

Most notable of these – and given the most attention – has been Ukraine’s application to join NATO, in response to Russia’s internationally condemned attempts to formally annex occupied Ukrainian territory. While this is certainly worthy of analysis, this piece will also take a look at some of the other proposals that have been made that aim to formally guarantee the security of Ukraine.

Ukraine applies to join NATO

On 30th September 2022, Ukraine formally requested an “accelerated accession” to join NATO – in response to Russia formally declaring its annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts. Russian President Vladimir Putin had earlier the same day held a signing ceremony in Moscow with the putative heads of these states, following referendums in Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson – almost universally condemned as a sham by the international community.

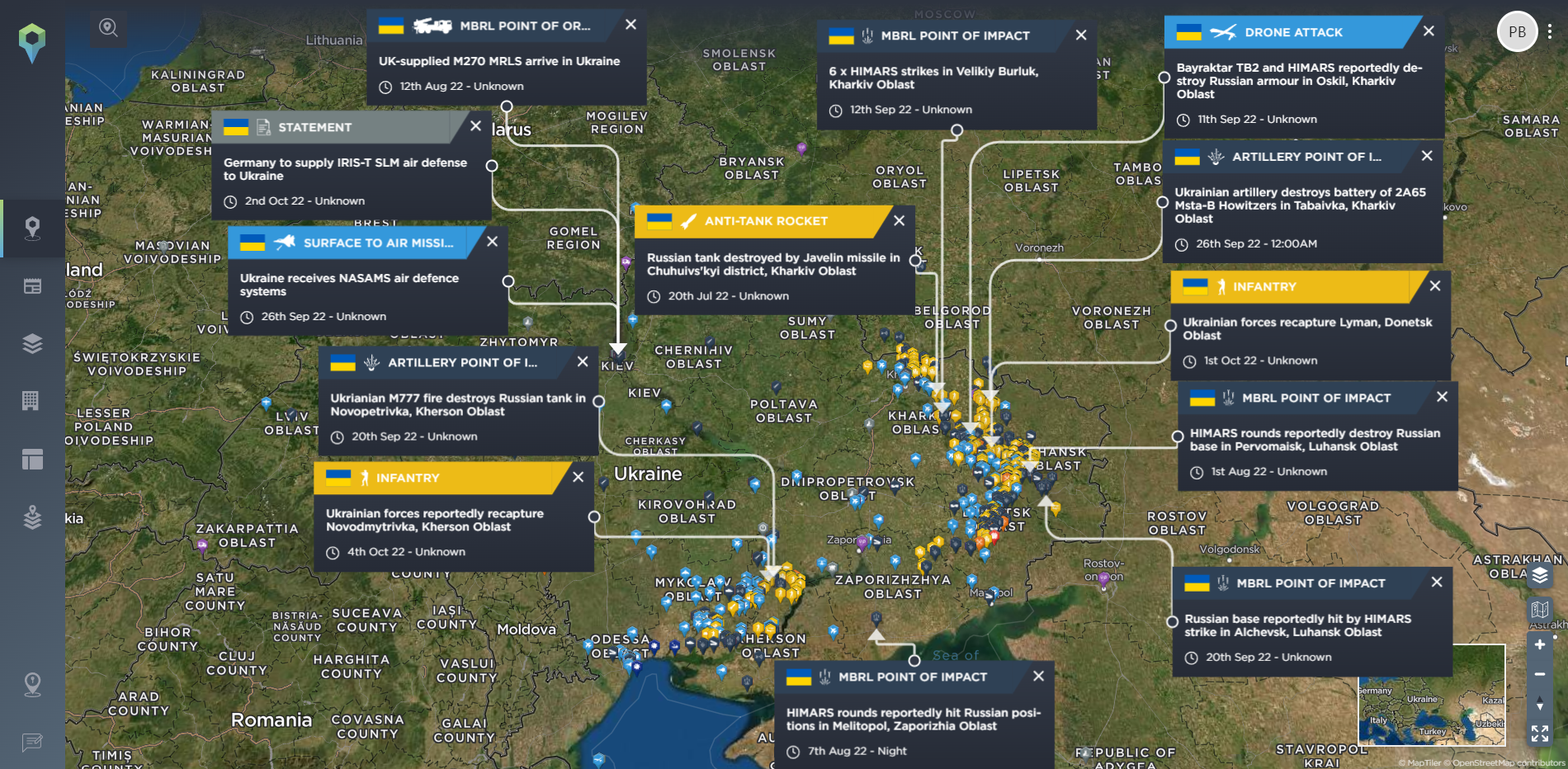

Ukraine applied to join NATO following Russia's annexation of significant parts of Ukraine's territory [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

While the announcement that it was seeking an accelerated membership of NATO was likely in part designed to distract from Putin’s grandstanding speech and signal a note of defiance in the face of the illegal annexation of 15% of Ukraine’s territory, it was also the latest in a long process of Ukraine potentially joining NATO – and of tensions between Russia and the alliance. As far back as 2008, NATO allies had signalled that Ukraine could eventually become an alliance member, while NATO’s eastward expansion has been labelled an ‘existential threat’ by the Kremlin, who had demanded binding guarantees that Ukraine would not join prior to launching its invasion in February.

What are the requirements for NATO membership?

NATO has an open door policy. That is, any European country is free to apply, and members are free to leave if they would like. However, in order to be accepted, there are certain requirements that need to be met, based on the results of a 1995 Study on NATO Enlargement. These are:

- a functioning democratic political system based on a market economy;

- the fair treatment of minority populations;

- a commitment to the peaceful resolution of conflicts;

- the ability and willingness to make a military contribution to NATO operations; and

- a commitment to democratic civil-military relations and institutional structures.

Will Ukraine join NATO?

Almost as soon as President Zelenskyy had announced his formal application, NATO appeared to distance itself from the possibility of this happening any time soon.

In a press conference just hours afterwards, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said that while “every democracy in Europe has the right to apply for NATO membership”, and that NATO members “support Ukraine’s right to choose its own path, to decide what kind of security arrangements it wants to be part of”, he reiterated that any decision on membership “has to be taken by all 30 allies, and we take these decisions by consensus”, adding that NATO’s focus in the immediate term is on the war itself and providing Ukraine the support it needs now. He reaffirmed this position almost word for word two days later on an appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press. Based on this, any fast-tracked accession would seem unlikely.

Further, such an accelerated accession would be unprecedented for NATO; it is usually a lengthy process that involves a period of ‘Intensified Dialogue’, joining a ‘Membership Action Plan’, and, as mentioned above, must be signed off by all 30 NATO members. For example, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (now North Macedonia) joined NATO’s partnership for peace in 1995, and joined the Membership Action Plan in 1999 – it did not become a NATO member until 2020 and it had resolved a dispute with Greece over its name.

Additionally, while the North Atlantic Treaty itself does not specify one way or another, no nation has ever been asked to join NATO that was party to an ongoing conflict. Even countries with portions of their territory under dispute are unlikely to be accepted. The Treaty specifies that it is a collective defensive alliance, and that it seeks the preservation of peace and security; with Article 5 agreeing that an attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against all of them, allowing the membership of a country already involved in armed conflict would therefore be contrary to its stated aims, as it would effectively risk immediately drawing 30 NATO countries into direct involvement in armed conflict, as opposed to maintaining peace. Again, while this would not be specifically in contravention of NATO’s membership criteria, it is likely to be enough of a sticking point to make the required unanimous support highly unlikely.

Given that it is unlikely that Ukraine would be invited to join NATO any time soon then, what other solutions have been proposed that would provide security assurances to Ukraine?

Prior to Ukraine's application for NATO membership, the Kyiv Security Compact had been proposed as a way forward towards formal security assurances for Ukraine [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Kyiv Security Compact

On 13th September 2022, a working group led by former NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh-Rasmussen and Head of Ukraine’s Presidential Administration Andrii Yermak released a report detailing a framework for how future international support can be provided to Ukraine. Titled the Kyiv Security Compact, it looks at “mobilising the necessary political, financial, military, and diplomatic resources for Ukraine’s self-defence. The Compact will consist of a joint strategic partnership document co-signed by guarantor states and Ukraine.” At the time of writing, this multilateral agreement remains a proposal.

There are several points to highlight from its key recommendations:

- The strongest security guarantee for Ukraine lies in its capacity to defend itself against an aggressor under the UN Charter’s Article 51. To do so, Ukraine needs the resources to maintain a significant defensive force capable of withstanding the Russian Federation’s armed forces and paramilitaries.

- This requires a multi-decade effort of sustained investment in Ukraine’s defence industrial base, scalable weapons transfers and intelligence support from allies, intensive training missions and joint exercises under the European Union and NATO flags.

- The Compact will bring a core group of allied countries together with Ukraine. This could include the US, UK, Canada, Poland, Italy, Germany, France, Australia, Turkey, and Nordic, Baltic, Central and Eastern European countries.

Additionally, the Compact proposes to have several legally and politically binding security guarantees for Ukraine along with a sanctions regime against Russia including ‘snapback’ or trigger sanctions should a specific event occur. The Compact also makes specific mention of the ‘Budapest Memorandum’ of 1994, referring to the ‘Memorandum on security assurances in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons’ – possibly the most significant existing assurance of Ukraine’s security.

What is the Budapest Memorandum?

The Budapest Memorandum is a document created and signed by Ukraine, the USA, UK, Ireland and Russia which enabled Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The memorandum came about due to concerns of nuclear weapons being possessed by Ukraine following the breakup of the Soviet Union. Ukraine agreed to send nuclear weapons in its territory to disarmament facilities in Russia and in return, it received guarantees from all signatories that no use of force or economic coercion would be used against it. Additionally, should any act of aggression occur against Ukraine, all the signatories would seek action from the UN Security Council (UNSC).

The 1994 Budapest Memorandum provided security assurances to Ukraine that have since been disregarded [image source: treaties.un.org]

The Kyiv Security Compact states that, “the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances proved worthless. No sufficiently robust, legally and politically binding measures were in place to deter Russian aggression.”

Given what has taken place in Ukraine, not just since the Russian invasion of February 2022, but dating back to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, it is difficult to argue with this point. Russia – like the UK and USA – has veto power on the UNSC. It has thus been able to violate the Budapest Memorandum with impunity as it can veto any action taken through the UNSC to protect Ukraine as per the Memorandum.

How does the Kyiv Security Compact compare?

At first glance, the Kyiv Security Compact would appear to be a comprehensive path forward for Ukraine. However, when taking a closer look at what it proposes, a number of points need to be made:

- First, and probably most important, this war is not over yet; it may take a number of years for it to even conclude given recent decisions by President Putin – let alone conclude in a way that sees Ukraine regaining territory. So this proposal is a little bit early to put forward.

- The Compact relies on the UN Charter, specifically Article 51, which states, “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security.” This is the same weakness the Budapest Memorandum has, as involving the UNSC means that any measures which may be undertaken can be vetoed by one of the P5 members – France, China, UK, USA and Russia.

Pledges to commit to sustained investment in Ukraine's defence industry, weapons, training missions and more would require significant funding at a time of widespread economic difficulty [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

- In relation to the multi-decade effort of sustained investment in Ukraine’s defence industrial base, weapons transfers, intelligence support, training missions and joint exercises; all of these efforts will require significant amounts of money from signatories; all of whom will only be able to provide such money from the taxpayers within their own nations. And those taxpayers right now are noticing significant problems with inflation, cost of living, cost of doing business and energy supplies – exacerbated by Russian counter-sanctions impacting the supply and price of energy. Russia may be cutting off the gas, but many states have also had a direct hand in creating these economic conditions through a lack of resilience in reliable energy supplies, natural gas especially, while the global economy is already reeling from COVID-19. So for any state that becomes a signatory, where will the money come from?

- Further to this, as brought up in an episode of The Roundtable podcast, for a lot of countries save for the USA, investment in their own defence and security has not been a priority for quite some time. So how can any investment, training or support in Ukraine be done if the defence sectors of many potential signatories have arguably been neglected over the years?

- The sanctions regime is also a cause for concern. In a prior episode of The Insight, one of Intelligence Fusion’s Regional Analysts, Camille Privé, summarised the current sanctions regime on Russia, describing them as tokenistic. Current sanctions have indeed hurt the Russian economy in a big way and Russia has not been able to make up for the losses through selling to Asian countries. However, Russia has been able to respond in kind to EU sanctions by cutting off natural gas supplies and recent developments have shown that President Putin and the Russian government have no intention of ceasing their invasion of Ukraine willingly. This has led to damaging economic consequences for all parties involved. A sanctions regime, if current conditions were to continue in the future, could therefore prove to be just as detrimental to potential signatories as they would be to Russia.

- Finally, the concept of legally and politically binding security guarantees is also flawed. At a basic level, proposals for legally and politically binding guarantees have no real threat of reprisal should a potential signatory disregard them.

These are just a few points which need to be made about this proposed Kyiv Security Compact. It’s a very ambitious document and given the correct conditions, it could be an effective way to deter further aggression from Russia against Ukraine. As prior analysis and ongoing monitoring of the war shows, the Ukrainians have been able to employ the military aid it has received; whether it’s Bayraktar TB2’s, Javelin or NLAAW anti-armour weapons, M777 Howitzers or M142 HIMARS, they have been adept at using them to fight Russian forces effectively, and the Kyiv Security Compact would have the potential to maintain that state of play. However, in its current form and with current realities, the proposed agreement is rather weak, with potentially some of the same major flaws seen in the Budapest Memorandum that the Compact is so critical of.

Ukraine has been very effective at using the military aid it has received [image source: Intelligence Fusion]

In summary, then, there are few straightforward solutions. NATO membership is surely off the table for as long as Ukraine is part of any active ongoing conflict – and would likely apply to any continued fighting in the Donbas region even if peace can be agreed with Russia. Beyond this, a unanimous agreement between all existing NATO members to grant Ukraine membership would be far from guaranteed in any case.

Russia’s place as a permanent member of the UNSC allows it to veto any security measures through the UN that would not be to its liking (and of course, the inverse is true of the US and UK too, should any hypothetical volte-face in relations occur in the future, however unlikely). This seriously undermines any proposals invoking Article 51 of the UN charter as a central tenet of their security assurances.

And the existing economic and energy difficulties of its Western partners, in addition to years of ignoring their own military capabilities, make funding any long-term guaranteed military supplies, training and investment extremely difficult – although there is clearly existing political will for the time being.

What is clear, though, is that Ukraine has proved itself a capable partner when it comes to utilising the assistance it has received. As winter approaches, on the ground fighting becomes more difficult and slows down, and frontlines potentially freeze in place until the spring, a key priority should be to ensure that Ukraine has the capacity to continue to do so long-term – while using a potential dip in direct hostilities as an opportunity to shape some concrete security assurances that would deter future Russian aggression. The proposals discussed above are a positive first step towards this.

Intelligence Fusion has been tracking the Russia-Ukraine conflict since its early beginnings, with a dedicated theme on our threat intelligence platform allowing our clients to easily filter down to incidents related to the conflict and track the latest developments. As the war heads towards winter, we’ll continue to monitor both the situation on the ground, as well as the wider geopolitical situation, and keep our users informed.

If you want to see the data supporting our analysis, and try the Intelligence Fusion platform for yourself, arrange some time to speak with a member of our team here.