Xi Jinping and the 20th Party Congress: Chinese politics and geopolitics in 2022

2022 will see China's 20th Party Congress take place, likely in the Autumn. With the Party Congress expected to further centralise Xi Jinping's control of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and therefore over the country itself, what will this mean for China's politics, society and economy - and Chinese geopolitics in the wider world?

The coming year is an important one in the world of Chinese politics. As the 20th Party Congress approaches, the smart money is on Xi Jinping breaking the tenuous convention on term limits and retaining his positions as President, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CCP) and likely Chairman of the Central Military Commission well into the 2020s, if not for life. While this could ensure continuity, given the characteristics of Xi’s rule to date – a shift towards greater authoritarianism and a decline in consensus-driven policy – it is far from a guarantee of stability. Xi appears to be animated by the need to tackle the big problems facing China – social, economic and security-related – that threaten to curb China’s rise and threaten the fulfilment of the so-called ‘China Dream’.

China's Internal Politics in 2022

A brief review of the last ten years of Xi’s rule gives a fairly clear idea of what this new era will look like. Throughout his time in office Xi has used his power to address what he sees as a slide towards liberalisation and away from Party rule, strengthen the armed forces while making exorbitant territorial claims, and subordinate business as part of reshaping the economy to better serve Party rule and stability.

As the princeling son of a liberalising Party grandee, Xi was expected to continue the trends begun in the 1980s of economic liberalisation under the banner of Reform and Opening Up. These policies were expected to lead to increased social and political freedoms in China, and to some extent this appeared to be the case under the leadership of Jiang and then Hu. Xi however seems to view this gradual liberalisation of Chinese civic society under his predecessors not so much as progress but as a threat to Party supremacy. Rather than allowing Chinese society to liberalise, after consolidating power with a ruthless efficiency unseen since Mao, Xi has driven the return of the Party, or as he phrased it following the 19th Party Congress: “Party, government, military, civilian, and academic; east, west, south, north, and centre, the Party leads everything.” A return to Party centrality may not be viewed as particularly concerning to many. Indeed, given China’s status as a one-party state this point could come across as banal, especially as the Party was never looked to have gone very far. Of concern is not so much the centrality of the Party – but the dictator-like centrality of Xi to the Party itself, and the end of the collective decision-making process which supposedly characterised CCP policy making.

“Party, government, military, civilian, and academic; east, west, south, north, and centre, the Party leads everything.”

Since taking power in 2012, Xi and his supporters have moved to establish him as the most powerful leader since Mao. He weaponized anti-corruption to wage a campaign against rival faction members and bypassed the traditional collective decision-making process through the establishment of leading small groups, which he invariably chairs, to set policy direction. The promotion of trusted subordinates to positions of influence has entrenched Xi and his faction in all the important positions of government and Party. His theoretical contribution – a necessary accolade for a CCP leader’s credentials – Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era (aka Xi Jinping Thought) was included in the Chinese constitution at the 19th Party Congress. Previously only Mao had this honour, and the inclusion of Xi’s political theory ensures that his ideas will be a force in Chinese politics even after his death. This legacy was further burnished at the Sixth Plenum in November last year with the adoption of the Party’s third historical resolution. Just as the previous resolutions drew a line and established an official history of the periods covering Mao’s rise and then later rule, effectively wiping the slate clean in order for China to move into the era of Reform and Opening, this new resolution closes the book on the period begun by Deng in favour of a new era, defined by Xi Jinping and his Thought.

Such a consolidation of power and status has allowed Xi to carry out his agenda, with seemingly little opposition. While there continue to be glimpses of factional infighting and even the occasional, unconfirmed rumour of plots and coup attempts, it would seem that Xi is able to rule without significant challenges from within.

Chinese Economy and Society

Xi has used this power to constrain Chinese society within the bounds defined by the Party. For example, rather than being the liberating force people expected, the spread of the internet in China has enabled the creation of sweeping state surveillance and control reaching deep into all aspects of Chinese society. This technology has reached its height in the regions of Xinjiang and Tibet, where the oppression of the non-Han populations has reached new levels of sophistication, brought widespread condemnation for the Chinese regime, and caused not-insignificant reputational risk for the many Western companies whose supply chains lead there. Beijing’s harsh assertion of control in Hong Kong and establishment of a de facto police state in the city has also gained global headlines and caused some multinationals to question their presence there. The introduction of the Social Credit system, crackdowns on celebrity obsessions, incentives to have more children (in an effort to counter China’s impending demographic crisis), and even a directive to make Chinese men more ‘manly’ in the face of a perceived ‘sissy’ culture show a Party and leader determined not just to control Chinese society but to remake it.

Of greater concern to global business is the change of direction the Chinese economy is undergoing. While some prominent financial figures continue to bet big on China, others are increasingly wary in the face of dangerous levels of debt and state interference. As the economy has slowed, faced with the pandemic-induced global downturn and saddled with heavy debt, and with the early gains of urbanisation and industrialisation largely achieved, China finds itself in search of a new economic model to create continued growth. In a break from the Dengist approach of growth at any cost, Xi has introduced the somewhat contradictory policy of “Dual Circulation” in an attempt to maintain Party legitimacy by achieving continued growth and insulating China from shocks in the global economy, which is still reeling from the second once-in-a-lifetime crash in little more than a decade.

With more billionaires than any other country on earth, wealth inequality has become an extreme problem in China and a challenge to Party legitimacy that no one could have seen coming a few decades ago. This inequality is no doubt a factor behind the as-yet ill-defined policy of “Common Prosperity” that has driven the recent crackdown on tech companies and billionaires alike. While not seeking a return to the Chinese planned economy, Xi is clearly intent on maintaining control over key industries and subordinating the large private enterprises to state authority. As the treatment of the Ant Group IPO in November 2020 and Jack Ma’s subsequent acts of contrition ably demonstrate, Xi is unafraid to move decisively against the rich and powerful should they challenge the Party. Clearly wiping $1.5 trillion off the tech sector and sending investors running for cover is a price worth paying.

A selection of Chinese political, economic and social developments under the last 18 months of Xi Jinping's leadership [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

Chinese Geopolitics and Foreign Affairs

On the international stage the Xi Jinping era has seen an end to the principle of ‘hide and bide’ which governed China’s foreign policy for years. Whether in the form of ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy waged primarily on Twitter or the aggressive annexation and militarisation of the South China Sea, Chinese geopolitics have not been afraid to assert China’s agenda and dissatisfaction with the established international order. As a result it is facing an increasingly complex strategic environment, which is in no small part of its own making. The punitive trade tariffs China imposed on Australia following its calls for an enquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic exposed the willingness of China’s to weaponize its trade relations. Concerns of Chinese power have since led to the formation of the new AUKUS security partnership, and other regional actors are finally seeking to counter China’s growing military strength and territorial claims. While Japan has approved record defence budget spending and is looking to develop a conventional strike capability, the Philippines’ president Duterte has abandoned his tilt towards China and confirmed the planned purchase of the Indian/Russian BrahMos anti-ship missile in a clear effort to deter Chinese territorial claims in the South China Sea.

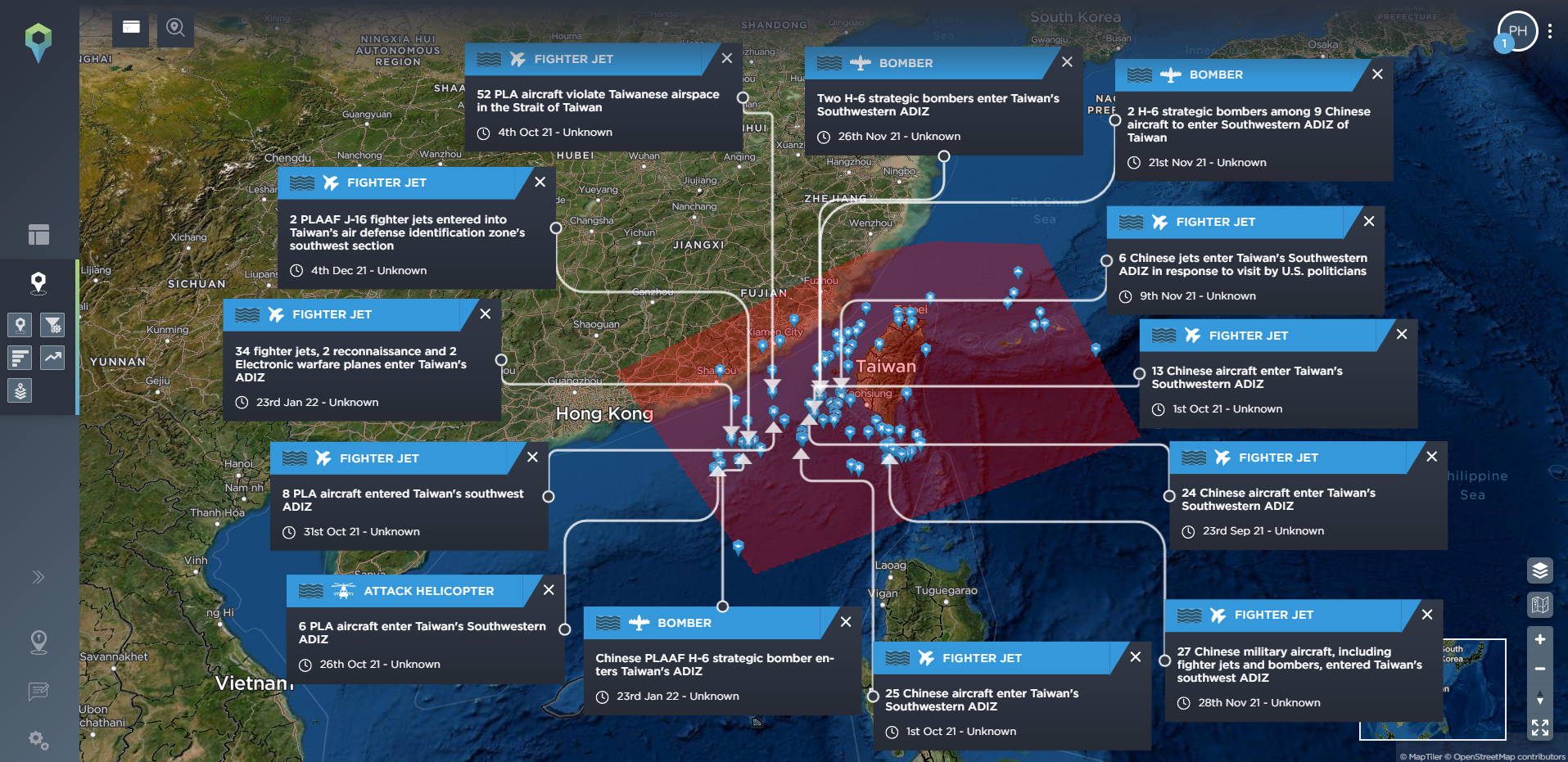

Additionally, reunification with Taiwan, as the summit of China’s nationalistic ambitions, is increasingly in the spotlight and has become a point of friction in U.S.-China relations once more. While the inability to launch an invasion has long made a virtue out of the necessity of Chinese restraint, there is a sense that as the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s military capabilities and Xi’s appeal to nationalism grow, patience and the long espoused commitment to peaceful reunification may be beginning to wear thin. Despite advances, China’s ability to launch such a reunification effort remains insufficient – for now – but the potential global impact a conflict over Taiwan would have means the issue requires serious attention. Indeed, it is not difficult to imagine any number of scenarios where Beijing – whether drunk on overconfidence or desperately appealing to nationalism to shore up support – decided to bring the Taiwan issue to a conclusion one way or the other. Until the final showdown does take place, China is increasingly prepared to engage in intimidation tactics towards Taiwan, sending an increasing number of jets and bombers into the the Taiwanese Air Defence Identification Zone when they wish to demonstrate their displeasure. Although a long way from an invasion, these incidents pose a real risk of an accident or misinterpretation leading to a significant incident that fixes the world’s attention on the strait.

Chinese aircraft frequently engage in intimidation tactics towards Taiwan by buzzing Taiwanese airspace [Source: Intelligence Fusion]

In the face of all these developments it is clear that Xi believes himself to be the man to guide China in 2022 and long beyond. To do this he may secure an additional term as General Secretary while arranging a suitable successor, withdraw behind the scenes to act as power broker (although this seems unlikely), or even reconstitute the office of Party Chairman to rule from a position of unassailable power. Either way we will not know for sure until the new Politburo Standing Committee walks onto the stage in the Great Hall of the People this autumn. Whatever his official title may be at year’s end, barring an accident or ill health it seems highly likely that Xi Jinping will remain the most powerful figure in Chinese politics for some time to come. Having so much power rested in one man is not without risk. Xi Jinping turns sixty-nine this year, and while he appears to be in good health the possibility of him dying in office and quite possibly without a clear successor is a legitimate cause for concern. China is not a country known for its smooth power transitions, and if something were to happen to him, without a strong and established heir it is unclear what Xi’s legacy would be, and when a dictator dies in office it seldom leads to the rise of a more moderate reformer.

With Xi and his Thought dominant it seems likely that the coming years will see continued pursuit of the yet-to-be-defined China Dream, with a reformed economy of subordinated business, totalitarianism at home and an increasingly powerful military pursuing a nationalistic foreign policy abroad. Whether his approach will successfully navigate China through the social, economic and international problems it faces to emerge as a prosperous superpower will only be seen with time, and the risk that China could push too hard and spark an economic or even military backlash will likely increase over the coming years as we have already seen resistance to the Chinese agenda begin to crystallise. If Xi Jinping’s first ten years are anything to go by, it’s likely that there are some interesting times to come.

As the year progresses and the 20th Party Congress draws nearer, we’ll continue to monitor developments in China and across the globe; follow us on Twitter to stay up to date with the latest threat intelligence insights or book a demo of our platform to learn more about mitigating risk in your business.