The social risks driving conflict with the mining industry

Identifying some of the biggest social risks to mining operations, and why Environmental, Social and Governance issues are one of the biggest threats that mining companies now face.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues are increasingly becoming one of the biggest risks to mining companies and their operations, and are now consistently identified as one of the most pressing concerns for industrial miners. In fact, according to a 2021 study published by Ernst & Young (EY), losing social support, or social license to operate is now seen as the main risk mining firms are facing. This means that mining companies now need to go beyond simply identifying technical and security risks to their operations, and instead make sure that they are fully aware of the social risks that can drive conflict with their operations – and have the necessary procedures in place to mitigate them. Failure to properly account for ESG risks can mean mining operations might face regular protests, closure of or failure to set up operations, and even lose the viability or control of their mining projects. This report will identify 5 of these key risks to the mining industry, and the impacts they can have on mining operations if not properly addressed.

Local population concerns

It is quite common for local populations to fear or be hesitant about the disruption that a new mining project may cause. In many new mining operations, there may be a local population currently living on the proposed mining concession, meaning that they will have to be compensated and relocated to make way for the project, which understandably can be met with resistance by those living there. However, even when relocation is not necessary, the reputation of the industry for causing damage to the local environment can cause resistance from the local population. Protests can be expected if the mining company does not implement high – and continuous – transparency and accountability measures, with effective communication and dialogue with the local community.

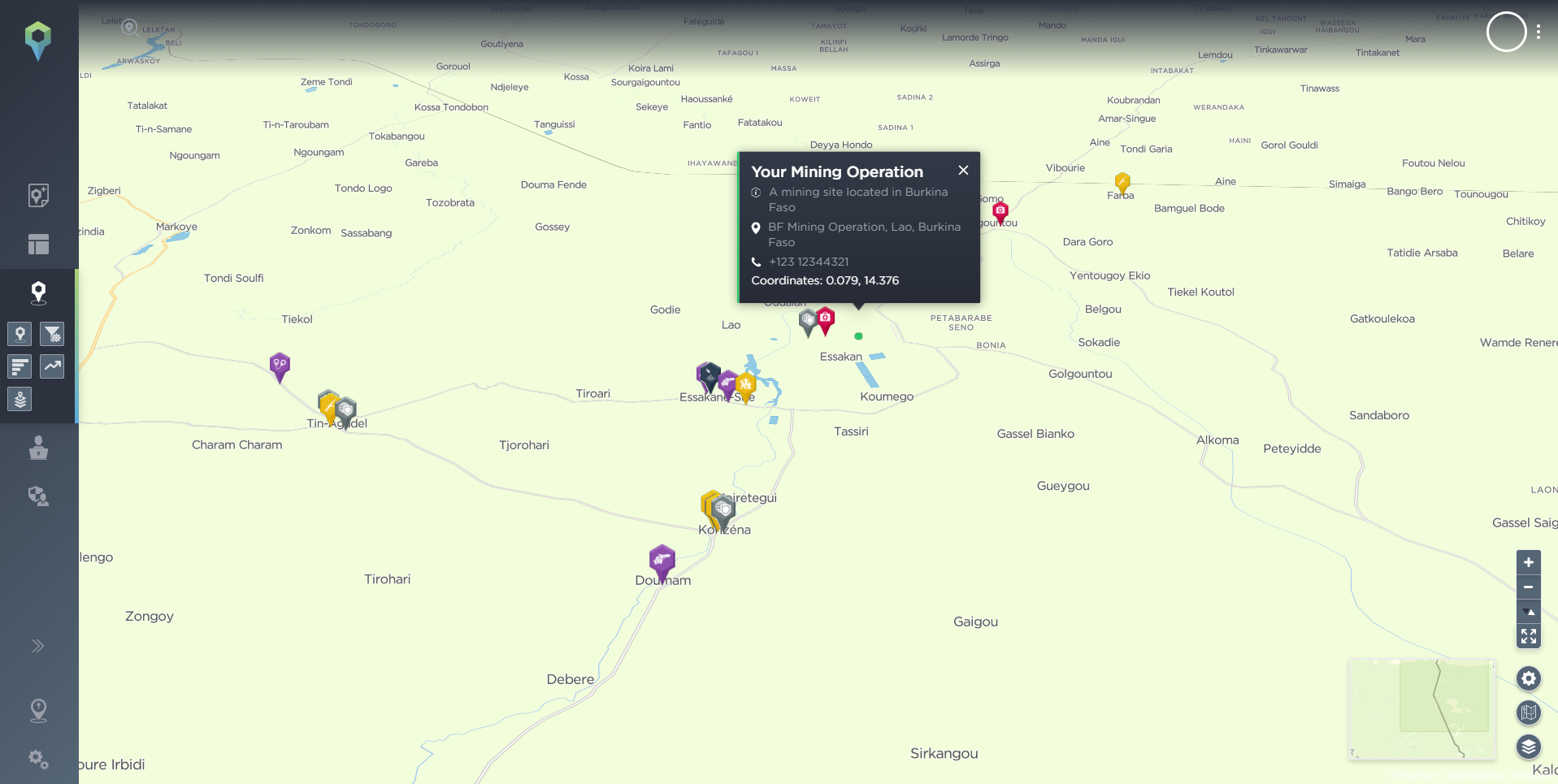

Incidents of protests against mining operations carried out by local populations in the Americas [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

As well as damaging the industry’s reputation and causing issues towards prospective mining projects, environmental damage can cause significant problems for the mining operation itself. Industrial accidents, malpractice or other actions that lead to pollution, contamination and environmental damage severely erode a company’s social license to operate, potentially causing irreparable damage to the relationship with the local population, and leading to widespread protest actions. It can also lead to increased resource nationalism sentiment (something which will be explored in greater detail later in this report), and regulatory action against the company and its operations.

Another key factor to be aware of is the rights of indigenous communities. When valuable mineral resources overlap with ancestral indigenous lands there is the strong potential for conflict – failure to work with indigenous communities in these instances can cause severe consequences for the mining company. The recent well-publicised case of Rio Tinto destroying historic Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) aboriginal rock shelters in Northern Australia was a clear example of a company failing to understand or address the concerns of the indigenous population, leading to a decision that proved both disastrous for the PKKP community and, from both a reputational and financial standpoint, severe for the mining company itself. Actions against a mining company failing to operate with care on indigenous lands can include road blockades, protests and the occupation and shutdown of mining sites, or, if the plan itself has not fully considered the indigenous population, attempts to prevent the mining set up in the first place. A separate, but linked, issue is that of the different ethnic groups that make up the local community. As will be explored later in this report, it is vital that a company looks to provide a high level of financial benefit to the local population, particularly with employment opportunities, but this must be done in consultation with local community leaders – tensions can arise if a certain tribe or ethnic group is perceived to be receiving favourable treatment.

Water insecurity is another key environmental concern to be aware of, and a frequent driver of conflict. Well-publicised and reputationally damaging incidents of malpractice or industrial accidents such as water contamination or dredging are obvious factors for causing conflict with the affected population, but are also a key driver of anti-mining sentiment and concerns that lead to populations resisting proposed new mining operations. The sector’s potential to pollute both ground and surface water is high. Moreover, access to water itself is a key driver of conflict – many mining activities require large amounts of water, while also often taking place in areas of low water availability; diverting water away from the local population to carry out this activity can cause large-scale, long-term conflict. In the Imider region of Morocco, for instance, where Africa’s largest silver mine is located, the indigenous Amasigh community has reported significant difficulty in accessing water, where it has either been diverted to mining activities or reaches the community with high levels of pollution, seriously affecting agricultural activity. For eight years, from 2011-2019, activists from the community occupied the Aleppan Mountain above the mine, cutting off a pipeline delivering water to it, and impacting its ability to operate.

Climate Change activism

Water insecurity is likely to become an ever-worsening problem as a result of climate change, and, as the mining sector operates in many of the areas likely to be badly affected by depleting water supplies, it’s therefore likely that climate change will cause a number of problems for the industry linked to the scarcity of resources, worsen any existing conflicts and lead to new conflicts related to water security where presently there are none.

While that is a potential long-term concern, in the present day there is the issue of climate change activism that causes conflict for the mining industry. Fossil fuel companies – particularly oil and gas firms, but also those involved in mining fossil fuels such as coal – have been repeatedly targeted by activists from groups such as Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion, including direct actions such as the blockading of facilities, demonstrations outside company headquarters and the storming of extraction operations themselves. Increasingly activists are also targeting financial institutions that are seen as financing and profiting from the fossil fuel industry in an effort to put pressure on these companies to divest their funding from extraction companies. This can potentially lead to challenges for extraction companies securing investment as these financial institutions impose certain conditions on funding, in order to alleviate any possible reputational damage as climate change activism and awareness becomes more and more part of the mainstream public and political agenda. In terms of mining specifically, coal mining companies are particularly vulnerable to climate change activism: there are reports that access to capital is diminishing as a result of social pressure to divest coal investments, and protesters have repeatedly directly targeted coal mining operations, particularly in Western Europe and North America. As climate change continues to dominate the news agenda, and extreme weather events become more frequent, these activities are likely to become more common, bigger in scale, and more disruptive.

The green agenda does present an opportunity for mining companies though, as a turn towards green energy across global markets will see an increase in demand for mined materials, such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper and others, that are used in the green energy supply chain. If companies can ease environmental concerns around their extractive activities then climate change and environmental activists in general may become more supportive of their operations rather than antagonistic.

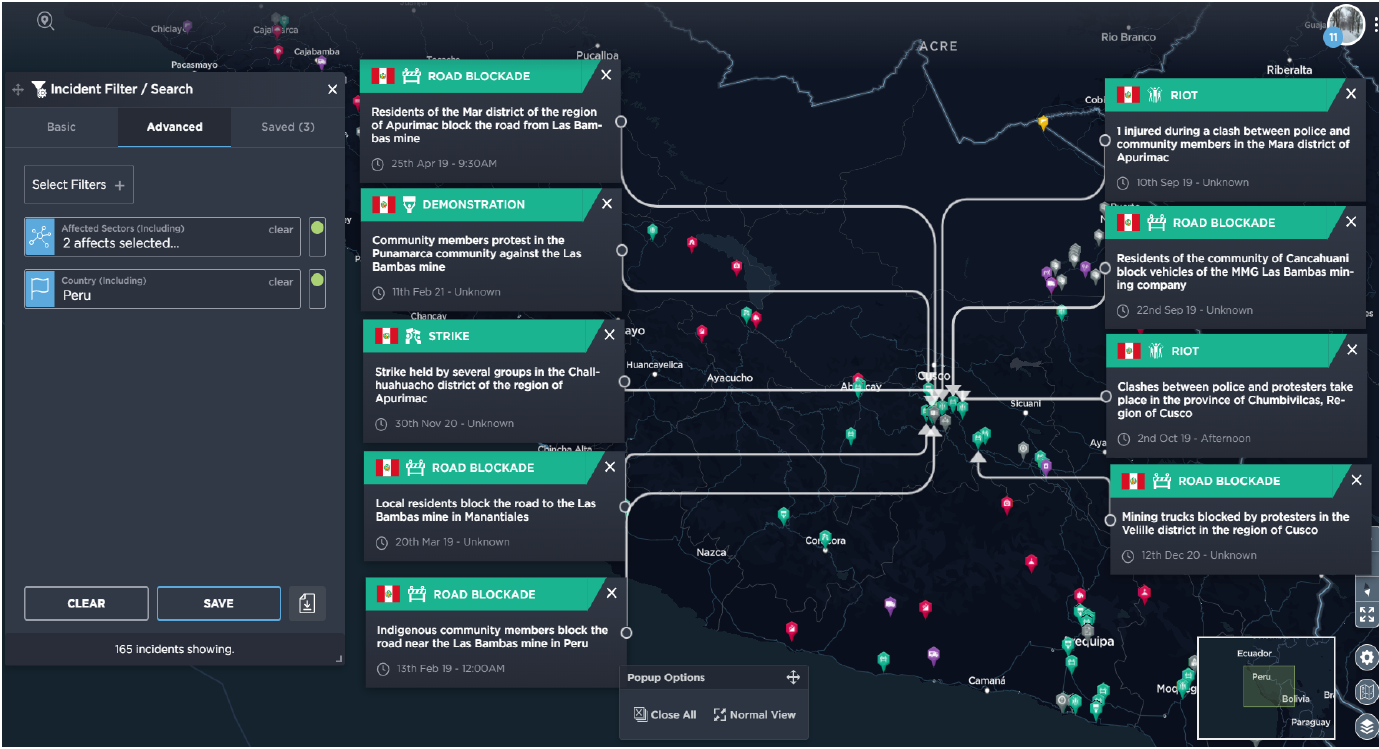

A proposed lithium mining project has been met with widespread protest in Serbia over environmental concerns [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

This could be complicated, though, by a reported ‘backlash’ towards the mining industry’s green credentials by existing anti-mining activists and critics, and concerns about the impact that some believe mining operations may have on the local area. Lithium mining in particular has come under scrutiny for the amount of water required, and the perceived potential damage to the local environment: in Serbia for instance, there is an ongoing protest movement attempting to prevent a planned lithium mining project in the country, while proposed lithium mining projects in South America also face potential resistance due to the ongoing drought and water shortages in the region.

Poverty and inequality

Many mining operations are based in countries that, while rich in natural resources, are poor in terms of economic development, with high levels of poverty and inequality in the local populations. This creates a number of issues that mining companies have to manage, with the potential for conflict and disruption to their mining activities, and, in some cases, threaten the viability of the mining operation entirely.

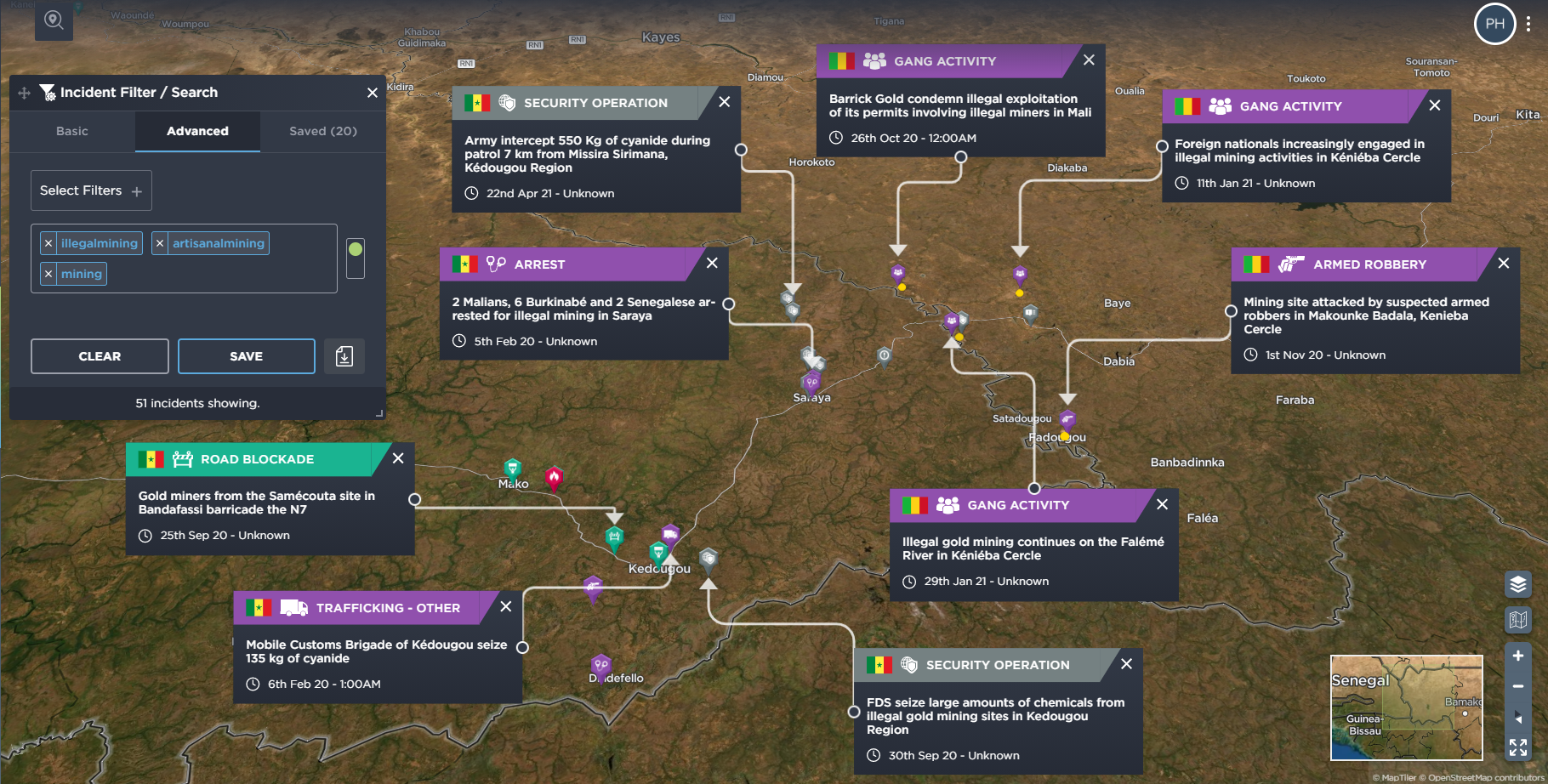

The most clear and obvious issue is that of Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM), which is widespread in the developing world. More than 40 million people are estimated to be directly involved in the sector; the World Bank estimates that around 100 million people depend on the sector when workers and their families are considered – this is compared to 7 million people worldwide in industrial mining. The overwhelming majority of these artisanal miners are stuck in the ‘poverty trap’, the desperation of poverty pushing them to work in what is a highly dangerous, unregulated and risky industry due to the higher potential earnings that can come from mining, but still unable to earn at anything above subsistence level. As well as the risks from dangerous working conditions, human rights abuses and child labour are also an all-too-common reality of ASM sites, which can also be used as a source of income for criminal or insurgent groups.

Developing countries with high levels of mineable resources, then, are often home to the concurrent sectors of ASM and industrial mining, with those involved in the former a potential source of conflict with the latter. Artisanal miners often encroach onto industrial mining concessions themselves, a situation that is fraught for mining companies – the potential financial loss, the potential damage to the mine and equipment, the potential environmental damage that can be caused by trespassing miners, as well as the potential harm that can come to the artisanal miners themselves, mean that illegal miners need to be deterred and/or removed from the mining site whenever encroachment or trespass occurs. At the same time, clashes between industrial mining site security or the country’s security services with artisanal miners can cause significant issues with the local population that damage the mining company’s social license to operate, and there have been a number of examples of the local population carrying out demonstrations or even riots towards mining companies following clashes with trespassing illegal miners.

Simply shutting down ASM sites however will simply lead to further resentment from a population that is reliant on mining as a key lifeline – as well as potentially driving many into criminality as a way to replace this lost income. Some companies are instead working with the population to help formalise and regulate mining methods and working conditions at ASM sites, creating a safer working environment for ASM miners, and a collaborative rather than antagonistic relationship with the local community.

This is a good example of the sort of work that industrial mining companies can do that simultaneously provides a social good for the local community while also helping to secure their own operations. The lack of development and high levels of poverty that can be found in many areas of industrial mining mean that a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) plan is essential – both to provide real benefits to the population as a result of mining activities, and as a way to therefore win over the community and secure the viability of the mining operation.

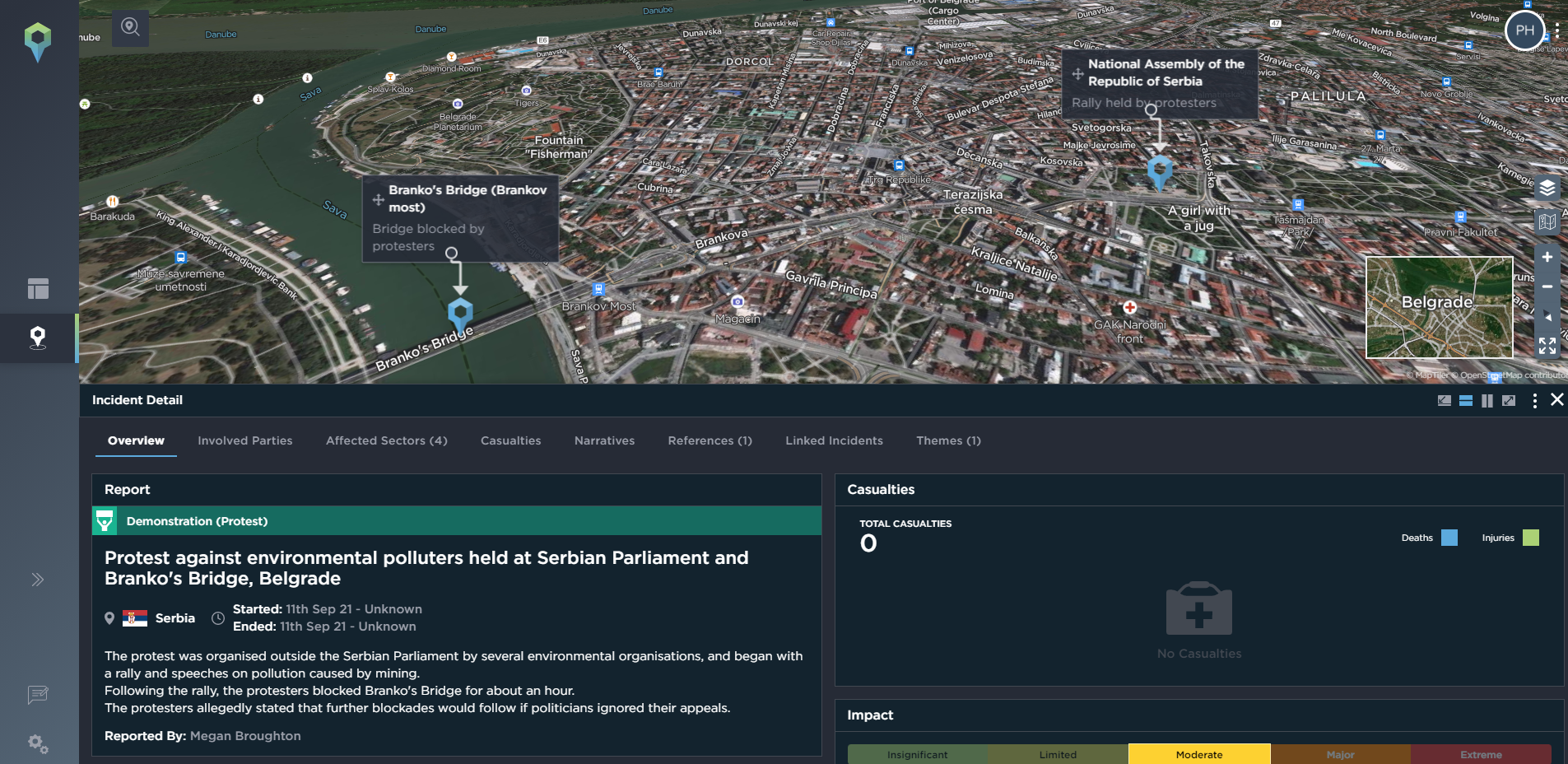

A weak CSR plan, and failure to win over or provide adequate financial or social benefits to the local population can cause protests against mining operations [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

The flipside of this is that a failure to provide an adequate level of CSR can lead to real consequences for the mining operation as a result of the local population feeling that the company has not met its social contract obligations. This perception – that the extraction company has failed to provide an acceptable level of CSR or tangible financial and social benefits to the local community – is a frequent driver of protest and conflict with industrial mining in developing countries, whether it’s dissatisfaction at the level of jobs available to the local population or a feeling that the company has reneged on agreements or promises made at the outset of the operation. In some cases – as we’ve seen with oil and gas operations in developing countries – local politicians and even militant groups can latch onto these grievances and issue threats towards companies.

Political instability

The other risk associated with operating in areas of low development and high inequality is a political situation that can be difficult to navigate. Miners have little choice with where and who they do business with, given that the overwhelming deciding factor for where to set up a mining operation is simply where the resources are located. This means in many cases having to operate in countries with low levels of democracy, human rights or, as mentioned above, economic opportunity. It can also mean operating in areas of high instability.

This is another reason why a strong CSR plan is so vital – in these areas of deprivation or weak state influence, a mining company can often be required to fill the void of the state itself, providing key infrastructure, education and healthcare projects among others, that might ordinarily be expected to be the state’s responsibility. As well as providing a social good, and, as highlighted above, fostering a positive relationship with the local community, it also helps differentiate the company from the state itself, something that might be important when operating in a country with, for instance, high levels of corruption. Rather than being associated with or being seen as enabling state corruption, something which would cause significant reputational damage and severely undermine a company’s social license to operate, the company can instead be seen as a separate, independent entity.

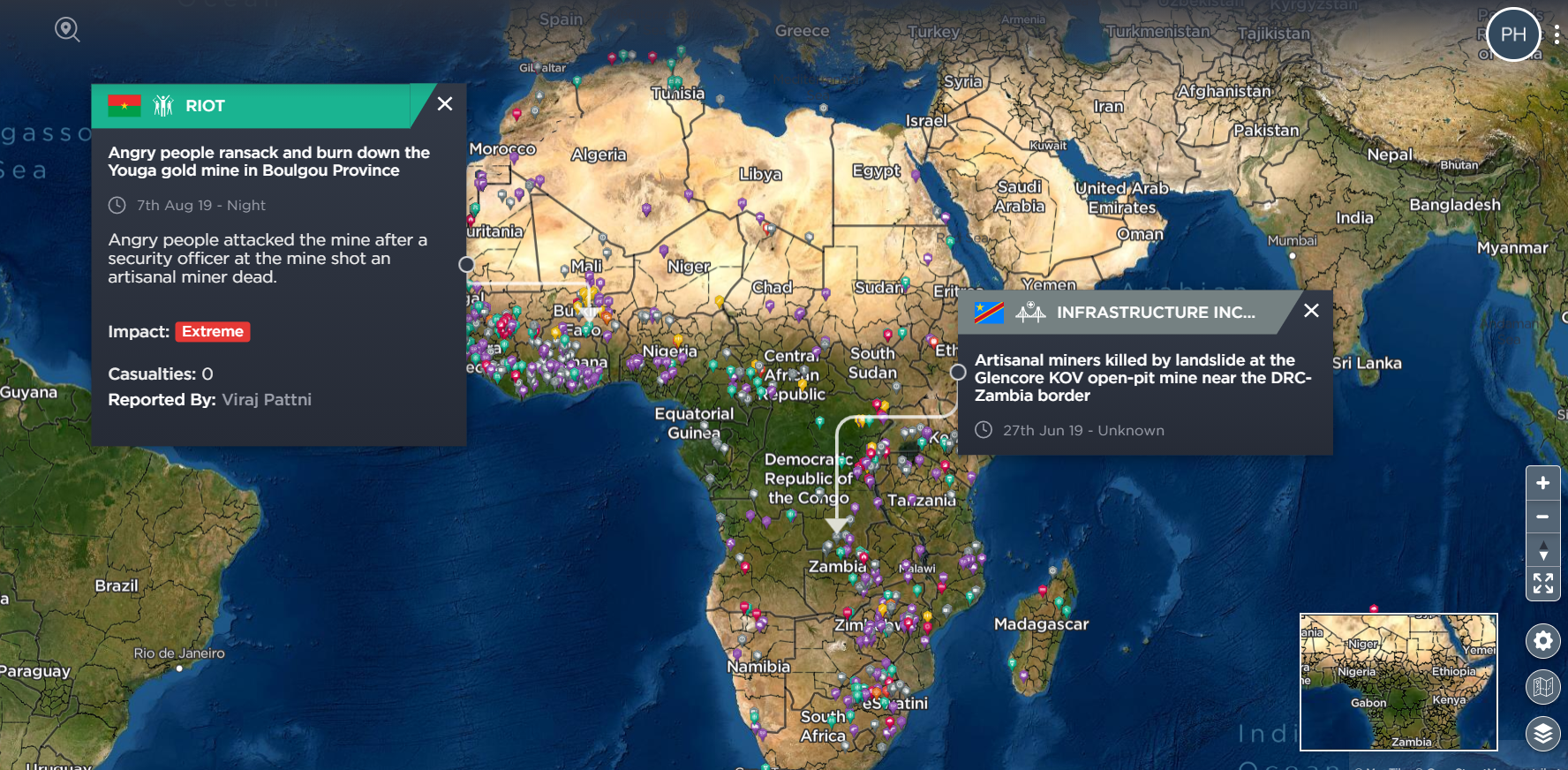

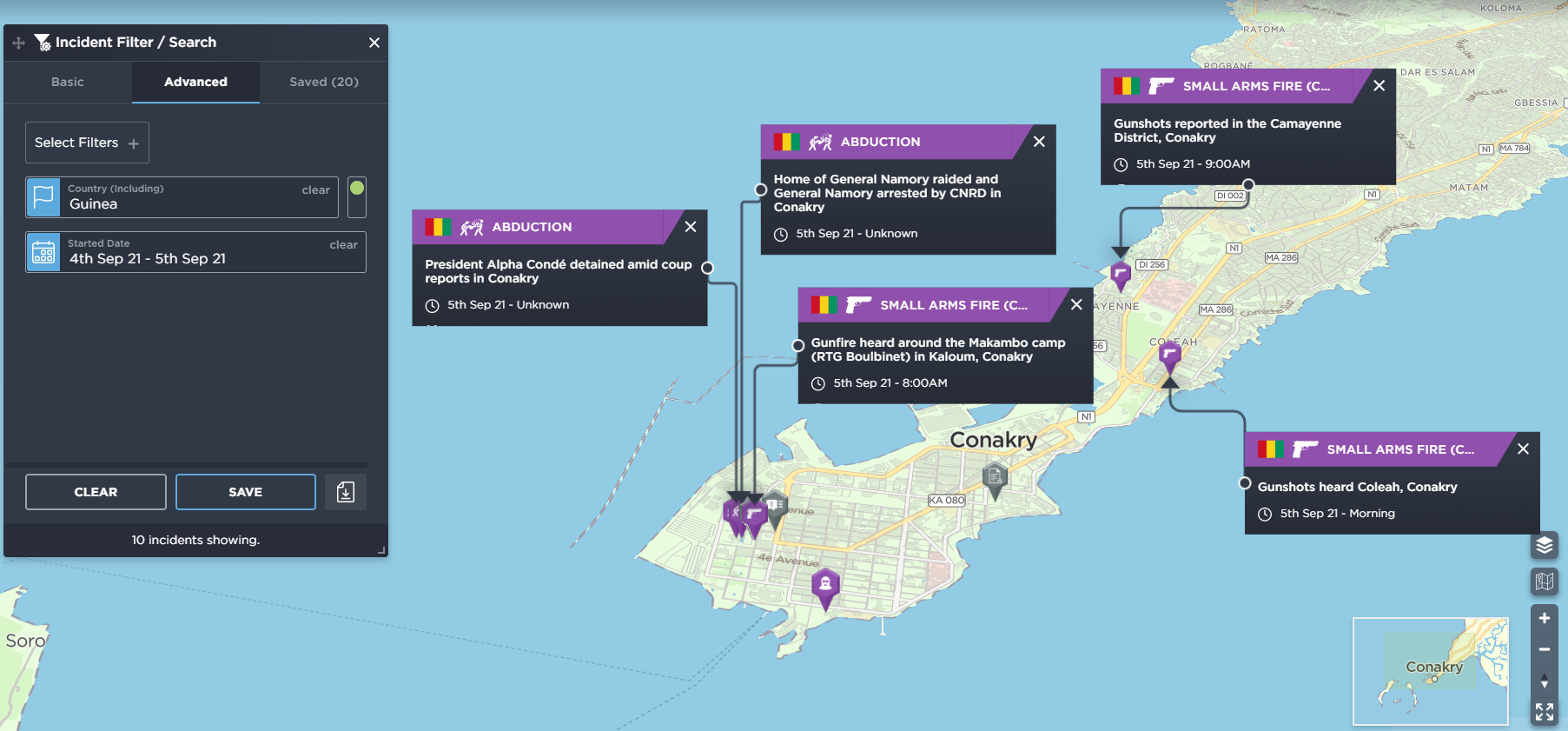

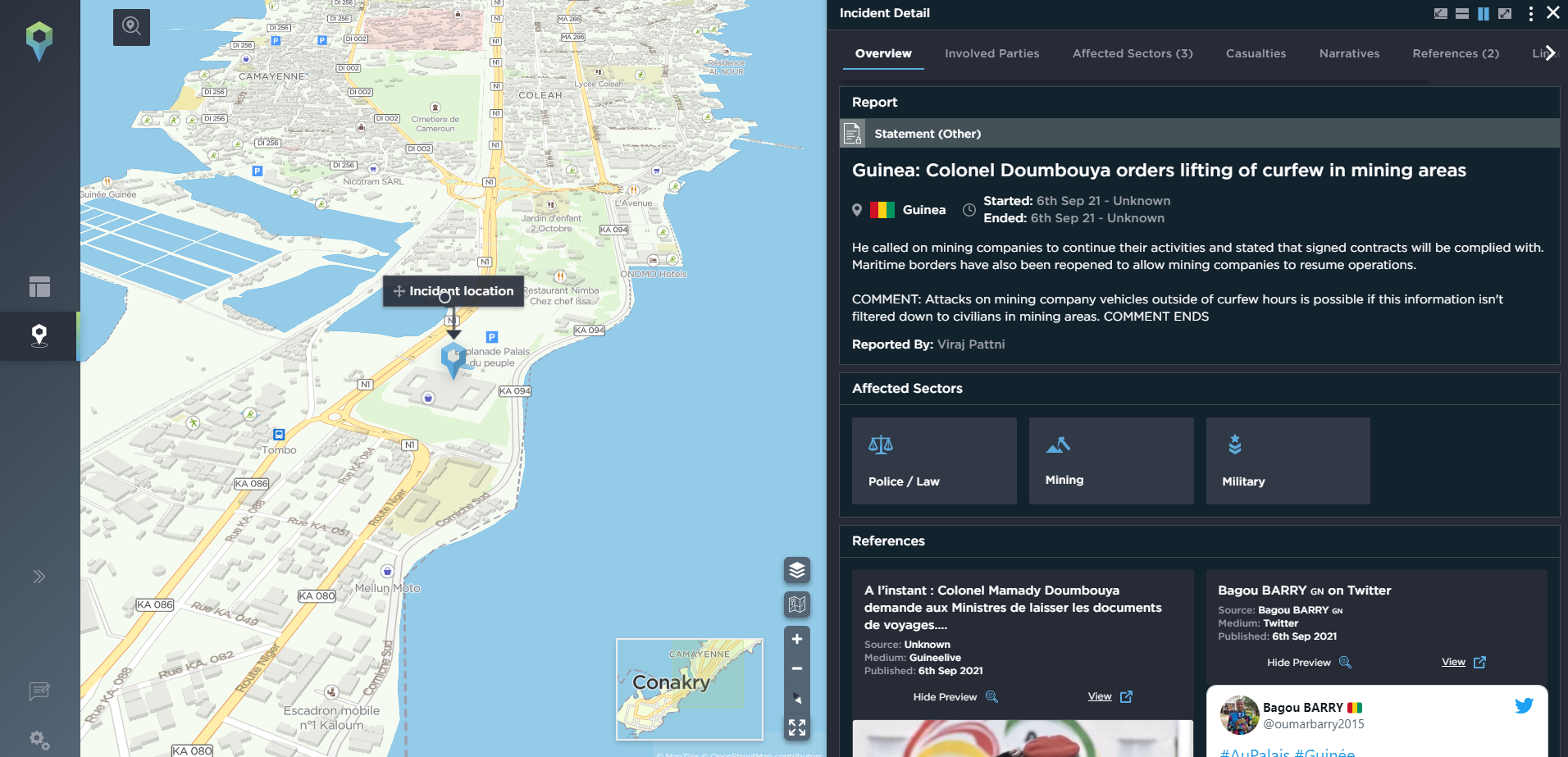

Political instability is a significant complication that a mining operation nonetheless has to prepare for when working in developing countries; with sudden and often unpredictable changes to governance a reality that mining companies have to deal with. Taking West Africa as an example, the gold-rich country of Mali has experienced two military coups in less than a year, with the military ousting President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in August 2020, and then again intervening and removing the interim President Bah N’Daw and Prime Minister Moctar Ouane in May 2021, this time appointing General Assimi Goita as head of the new interim government. In September 2021, neighbouring Guinea, which is home to some of the world’s largest bauxite deposits, experienced a military coup of its own, with special forces seizing control of the Presidential Palace and apprehending President Alpha Conde, and imposing a country-wide curfew. Both of these actions had immediate implications for mining operations in the countries – in Mali, share prices of gold mining companies operating in the country tumbled in the immediate aftermath of each coup; following the Guinea coup, prices of aluminium, which is made from refined bauxite, reached a ten-year high due to the uncertainty it caused.

It is also worth noting that new governments, especially in areas of instability and low economic development, may often seek to reexamine the high-revenue generating projects in the country, with mining projects often becoming a target for renegotiations, often forced on the companies, or expropriation.

Resource Nationalism

Resource nationalism is a trend that has been on the rise since the late 2010’s, with risk consultancy firm Verisk Maplecroft reporting that 66 countries have “witnessed negative shifts in the risk environment” since 2017. This appears to have become an even more pressing issue in the last 18 months to two years, with 34 countries “witnessing a significant increase in risk” since 2020. COVID-19 and its economic impact may have played a role in this, but a number of countries in very disparate parts of the world have turned towards resource nationalism, with some notable instances in 2021 alone – and the motivations pushing them towards it can vary.

Protests at the Las Bambas mine have been a frequent problem in Peru, which recently elected President Pedro Castillo on a left-wing, mine nationalisation agenda [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

Peru’s 2021 general elections saw the leftist populist Pedro Castillo win the Presidency, largely off the back of a platform that called for rewriting Peru’s constitution and nationalising foreign mining companies. Community members – particularly those in the region of Cusco – have repeatedly carried out protests against the Las Bambas copper mine, complaining about a lack of benefits for locals from the mining operation. Following Castillo’s election, in July 2021 residents of three communities in the Chumbivilcas province blocked the road from the mine, saying that they would continue to do so until a response was given by Castillo’s new government to their demands for greater benefits from the region’s mining resources. On 14th September the communities announced that they would continue their blockade following unsuccessful talks with the mining company (MMG Ltd).

In Kyrgyzstan, in May 2021, the Kyrgyz government seized control of the Kumtor gold mine from Canadian-based company Centerra Gold, accusing the company of abdicating its fundamental duties of care, and citing environmental and health concerns. The move came after the election of a new nationalist government led by Sadyr Japarov, a long-time proponent of nationalising the mine, who became President in January this year. In May, President Japarov signed into law a bill allowing the government to take a company and/or its concession under its control for three months if the company violates environmental regulations, damages or endangers the local environment or lives of people, or causes any other significant damage. Also in May, a Kyrgyz court ordered Centerra to pay a $3billion fine in compensation for environmental damages for the mine’s past practice of dumping waste rock on glaciers which feed the Naryn river, part of the Syr Darya, one of the main rivers in Central Asia. Parliament then approved introducing state management at the mine for three months – a state of affairs that remains at the time of writing. Local residents have argued that the mine has been responsible for increasing water shortages in recent years. Centerra Gold, however, has said that the true goal of this action is to justify the already stated desire to nationalise the mine or force the company to leave

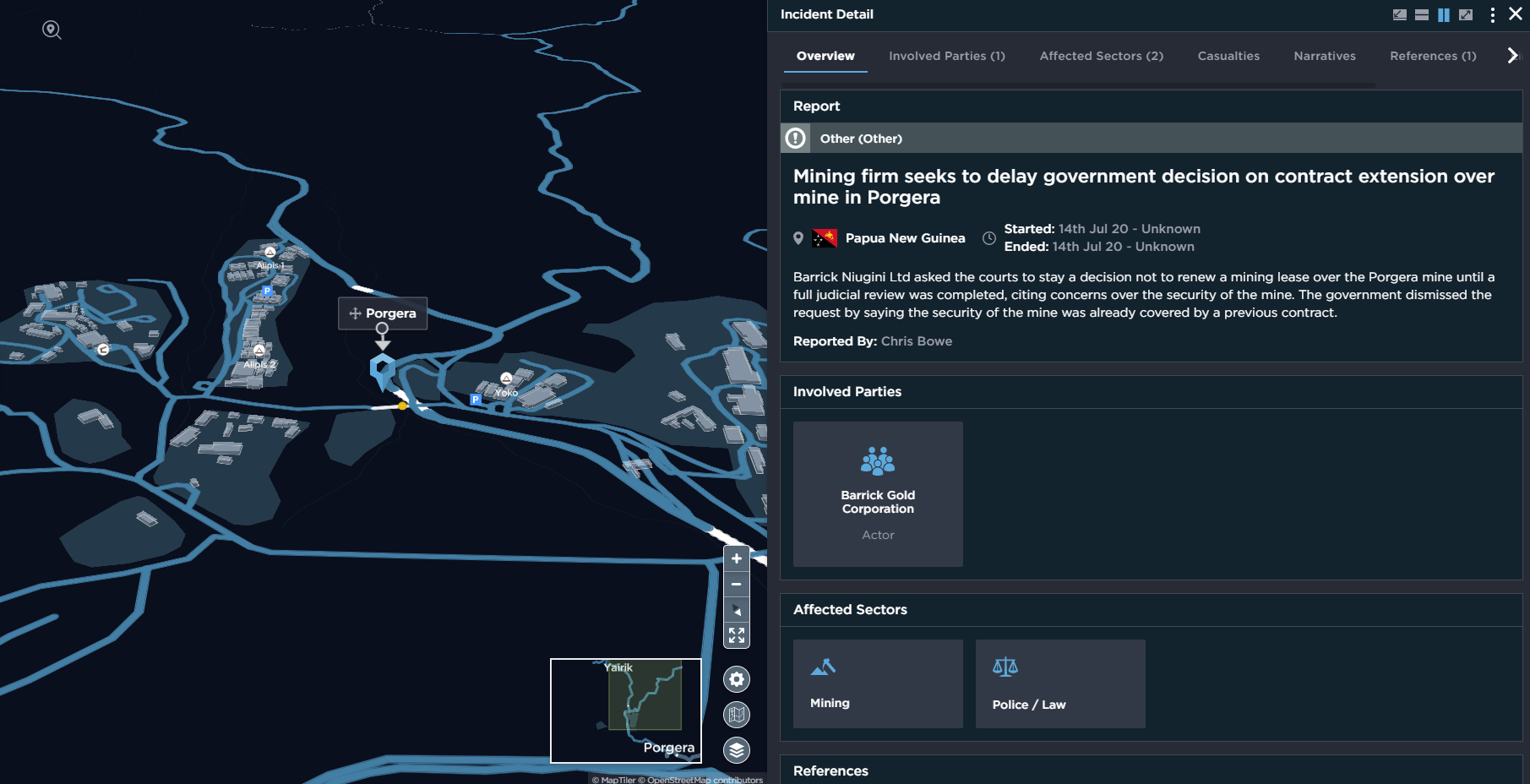

Prime Minister James Marape has sought to renegotiate mining contracts in Papua New Guinea, recently refusing to renew a 20 year lease on one of the country's largest gold mines until an agreement was reached 12 months later [Image source: Intelligence Fusion]

In Papua New Guinea, environmental, human rights and social concerns have led to a more nationalistic policy towards mining concessions from Prime Minister James Marape, sworn into office in May 2019. This led to the PNG government’s refusal to renew a 20 year lease for the Porgera gold mine with the Chinese state-owned Zijin Mining and its partner Barrick Gold Corp in April 2020 – Porgera is one of the country’s largest mining operations, and despite increases in gold prices the Papuan government closed down operations in the mine because of its environmental concerns, and social unrest from local landowners and residents. Negotiations did not lead to an agreement to resume operations until April 2021, with an increased holding in the venture for stakeholders in Papua New Guinea. The government has also passed the updated Mining (amendment) Bill 2020, which granted greater discretion to allot reserved land to majority state-owned ventures. However in June 2021, Prime Minister Marape spoke to reassure the mining and petroleum industries that the government was still in favour of foreign investment in the sector.

In Mexico, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (frequently referred to as ‘AMLO’) has put forward a legislative proposal to nationalise the country’s lithium resources – a proposal that has currently stalled but one that signals an intention to expand a nationalist intervention in the country’s resources in the second half of his term, due to come to an end in 2024. AMLO has already suspended the awarding of new oil and gas contracts to private sector firms upon taking office in 2018.

Causes of resource nationalism can vary, then, and often reflect the social factors outlined in the previous sections of this report – in some of the examples above it was related to a sentiment from the local or national population that they were not seeing enough benefit from the profits of mining operations; in others it was environmental concerns; in others it is simply more directly related to the political leanings of the governments themselves. A 2013 report from Zurich Insurance has also linked it to commodity prices, although it cites two different contradictory studies:

“Some studies demonstrate that periods of high commodity prices are correlated with increased expropriation of assets and investment disputes. For example, a recent Chatham House study on the political economy of natural resources states, ‘The propensity of a government to expropriate or intervene is often closely linked to resource prices. The recent upsurge in disputes and expropriations is reminiscent of earlier waves that also corresponded with periods of high resource prices. Compulsory nationalization or the assumption of a controlling interest, the confiscation of foreign-owned assets, windfall profit taxes and similar measures can therefore be expected to become more common in an era of high resource prices.’

Alternatively, lower commodity prices have also led to instances of nationalization where commodity-dependent governments have sought to maintain a certain level of income in the face of falling prices. This risk is particularly acute when there is a precipitous drop in prices and governments are suddenly faced with the challenge of meeting expansive budgets in the face of dwindling revenues”

It should also be noted that resource nationalism does not always manifest itself in the form of such direct intervention as the examples above – in fact, more often than not it is found in more subtle actions such as changes to the mining and tax codes in the host countries, increased levels of taxation or regulations, or class actions against mining companies based on alleged environmental or human rights breaches. This is known as ‘creeping expropriation’, as it essentially deprives the foreign company of the use or benefit of their investment, even if formally it still continues to belong to them.

ESG risks, then, can clearly cause myriad issues for mining companies, with the real threat of direct conflict with the local population, or the states themselves, a possibility if these issues are not properly managed or planned for. A high level of situational awareness is therefore necessary in order to monitor, track and mitigate the wide range of social risks that can face a mining company – which is why Intelligence Fusion tracks incidents relating to protest, political and governance issues, natural hazards and other factors, with the same level of detail and attention as we do direct security, weapons and criminal related incidents. In fact, we offer a high level of granularity with our data, with 159 separate incident types across 11 different categories, so our clients can dig deep into the different issues that they know can ultimately lead to high levels of risk to their operations.

If you’d like to learn more about the data that goes into our threat intelligence software, or see the platform in action for yourself, get in touch with a member of our team today.